Kennedy’s vision was accomplished by the Apollo 11 crew of Commander Neil Armstrong, Command Module Pilot Michael Collins, and Lunar Module Pilot Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin along with the thousands of support people on Earth. A little more than eight years after Kennedy made it the nation’s policy, Apollo 11 launched from Cape Kennedy on July 16, 1969.

From within the capsule attached to the top of the Saturn V launch vehicle, a rocket once described as a giant Roman candle, the rocket roared to life to lift the three pioneers into the final frontier. Even though the liftoff occurred at 9:32 AM in Florida, it was watched worldwide regardless of the local time.

Four days later, on Sunday, July 20, 1969, the world held its collective breath as the Lunar Module (LM), call-sign Eagle, was guided to the moon’s Sea of Tranquility and landed at 4:18 PM Central Time. Relief came when Neil Armstrong transmitted a message to Mission Control in Houston:

CAPCOM (Capsule Communicator) Charles Duke’s response summed up the feel of those of us on Earth as he stumbled a bit at the beginning:

According to the official schedule, Armstrong and Aldrin were supposed to get five hours of sleep. Realizing that it was unlikely they would be able to sleep, the crew prepared for the first walk on the moon’s surface.

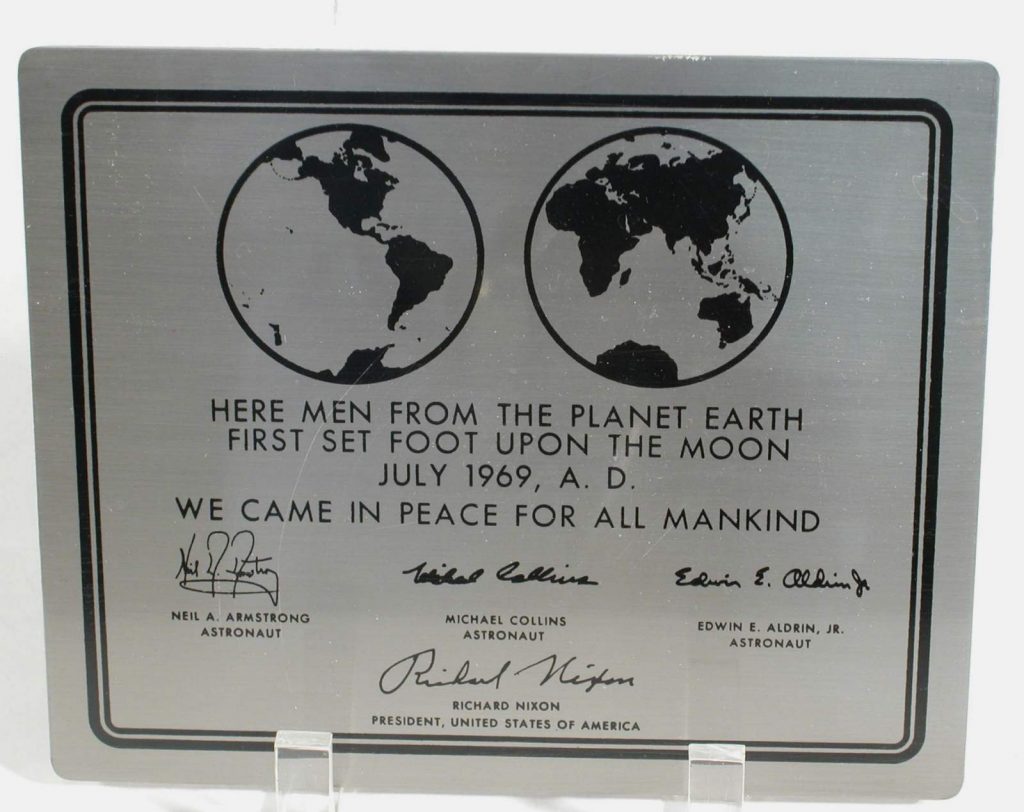

Six and a half hours after landing, after Walter Cronkite and the CBS News team showed models as to how Armstrong will descend from the LM, pull the D-Ring to activate the camera, Armstrong left the LM and went down the latter. He pulled the D-Ring, and the world watched his progress. Just before reaching the surface of the moon, Armstrong uncovered a plaque mounted on the LM that read:

Replica of the plaque on Eagle, the Apollo 11 Lunar Module (Courtesy of the Smithsonian Institute)

Armstrong looked at the surface and described the moon’s dust as “very fine-grained” and “almost like a powder.” Then with a short jump, he left the bottom rung of the ladder and was standing on the surface of the moon.

Over the years, there has been a debate about whether Armstrong included the word“a” in the statement. That is not what was heard at the time, and modern examinations of the audio tapes neither confirm or deny the claim. Regardless of what he said, Neil Armstrong was the first man to walk on the surface of the moon, a little more than eight years since President Kennedy said it was his goal.

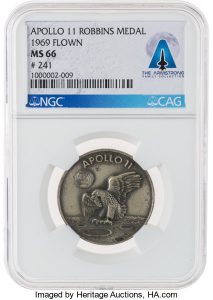

Apollo 11 Flown MS66 NGC Sterling Silver Robbins Medallion, Serial Number 241, from The Armstrong Family Collection (Courtesy of Heritage Auctions)

The practice of carrying Fliteline medals started in 1965 with the flight of Gemini 3, NASA’s first manned mission in the Gemini program. In 1968, the Robbins Company of Attleboro, Mass. was contracted to produce the Fliteline medals starting with Apollo 7.

It is reported that 480 of these 28mm medals were carried aboard Apollo 11.

According to Heritage Auctions, the most paid for a mission flown Robbins Medal was medal #241, a silver medal graded MS66 by NGC, that sold for $112,500 (including buyer’s premium) on November 1, 2018. It was sold with a Statement of Provenance signed by Armstrong’s sons as being once owned by Neil Armstrong. The provenance likely accounts for its high price.

In that speech at Rice University, JFK preceded those words with rhetorical questions about why people attempt doing incredibly difficult things, one including, “Why does Rice continue to play Texas?” The line got a polite chuckle.