This past week, I was looking into a box I purchased from an estate and I found a plastic bag of old foreign currency. When I removed the notes, I found common notes that can usually be purchased from estate especially since he was a career military officer. There was everything from German Notgeld to several European and Asian countries.

This past week, I was looking into a box I purchased from an estate and I found a plastic bag of old foreign currency. When I removed the notes, I found common notes that can usually be purchased from estate especially since he was a career military officer. There was everything from German Notgeld to several European and Asian countries.

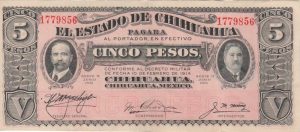

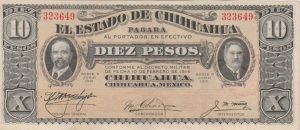

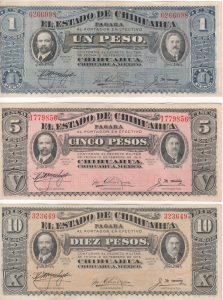

During my search, I found three notes that were intriguing. All three notes were from El Estado de Chihuahua, the State of Chihuahua. They were beautifully preserved (albeit with a fold down the center) one-, five-, and ten-peso notes with the same design but in different colors.

Under the printed denomination are the words “Conforme al Decreto Militar de Fecha Io de Febrero de 1914” (Pursuant to the Military Decree dated February 1914). I vaguely remember that was the era of Pancho Villa and his romp through the southwest United States. Time to refresh my history.

After the 35-yearlong regime of Porfirio Diaz, he was challenged in the presidential election by Francisco I Madero in 1910. Madero was in favor of reform and social justice. But Diaz fixed the election declaring he won by a landslide.

Before the election Diaz had Madero jailed and when it became obvious the election was fixed, Madero supporter Toribio Ortega formed a militia in Chihuahua to oust Diaz.

While in jail, Madero issued a “letter from jail” that declared the Diaz presidency illegal and called for a revolt against Diaz. The revolt began in November 1910. Diaz was ousted and a new election was held in October 1911 that elected Madero the 33rd President of Mexico.

Mexico was divided into districts managed by different governments and protected by rebel leaders including Pascual Orozco, Pancho Villa, and Emiliano Zapata. Eventually, they turned on Madero and assassinated him on February 13, 1913.

The United States first played a role in 1914 when Pancho Villa plundered parts of New Mexico. In 1916, Gen John J. Pershing was sent to Mexico to capture Villa but could not do so since Villa was hiding in the mountains of northern Mexico. Pershing was able to get some of the fighting to stop and, along with the Catholic Church and several affiliated political parties, forced the negotiation of the Constitution of 1917.

Although the notes were authorized in February 1914, the Chihuahua government did not have the ability to print notes. Eventually, they contracted with the American Banknote Company to produce the notes. They were issued in 1915.

To expedite production, all notes feature the same design engraved with different denominations and printed using different colored inks. Many of the elements used were standard to American Banknote’s catalog, for these notes, the portrait on the left is of Francisco I. Madero and the portrait on the right is Governor Abraham Gonzalez. Each features three signatures of the Tesorero General (General Treasury), Gobernator (Governor), and Interventor (Controller). As with many signatures, it is difficult to interpret their names from the handwriting. Please contact me if you have more information.

- Chihuahua Revolutionary 1 Peso Banknote. 1915 Series L (SCWPM #PS530e)

- Chihuahua Revolutionary 5 Pesos Banknote. 1915 Series N (SCWPM #PS532e)

- Chihuahua Revolutionary 10 Pesos Banknote. 1915 Series N (SCWPM #PS535a)

Reverse if these notes feature a framed picture of the Palacio de Gobierno do Chihuahua (Government Palace of Chihuahua) held by two griffins. When the notes were issued from the banks in Chihuahua, they received a red stamp from Tesorero General del Estado Chihuahua (General Treasury of the State of Chihuahua) along with the stamped initials of the issuing teller. When the notes were issued, the teller was supposed to stamp the date on the reverse but that was not universally practiced.

- Chihuahua Revolutionary 1 Peso Banknote. 1915 Series L (SCWPM #PS530e)

- Chihuahua Revolutionary 5 Pesos Banknote. 1915 Series N (SCWPM #PS532e)

- Chihuahua Revolutionary 10 Pesos Banknote. 1915 Series N (SCWPM #PS535a)

In addition to the one-, five-, and ten-peso notes, the Chihuahua government issued 20- and 50-peso notes as well as a 50-centavos fractional note. Both the 20- and 50-peso notes featured the same design except the 20-peso note was printed using brown ink and the 50-peso was printed with a bright green on the front and a golden yellow on the reverse.

The 50-centavo fractional note used a different design and was smaller than the pesos. It was also printed by the American Banknote Company.

These notes were demonetized in 1917 with the signing of the new constitution.

An Educational Opportunity

Money is history in your hands. Look at what can be learned from finding three banknotes and exploring their past and how they fit into history.

Here is an idea for history teachers: you can go to any coin show and find a dealer with a junk box of foreign currency—find more than one if you can to increase the variety. Pick through the box and try to find as many different pieces of currency you can. Try to find a mix of countries, regions, and dates. You can also consider the same country but from different eras of rulers, who always wanted to see their portrait on their country’s money.

Before going to class, place each note in an envelope and place the envelope in a bag. Either pass the bag around the room or have each student come up and pick one envelope. After they pick their currency note, have them write an essay about the note and what the note represents. Have the students look up the history and put it in context of when the note was issued.

Rather than picking a topic, it is a fun way to have the students select a topic and make history come to life. The decisions as to whether the students get to keep the currency are up to you. Maybe you can talk to a local shop or club to see if they would be willing to donate the currency and come in to talk about currency collecting.