Franklin Delano Roosevelt was inaugurated on March 4, 1933 at the height of the Great Depression. Unemployment was over 25-percent, inflations was rampant, farm prices have plummeted so low that it was cheaper for farmers to plow under crops, and banks were failing at record numbers.

Two weeks prior to his inauguration, FDR asked his old friend and Wall Street executive William H. Woodin, to be the Secretary of the Treasury and help implement a new monetary policy. Woodin rushed to Washington to work with Ogden Mills, President Herbert Hoover’s Secretary of the Treasury, in order to understand the issues. On the day of FDR’s inauguration, Mills resigned and voluntarily stayed in Washington to help Woodin with various policy changes.

Hours after FDR’s inauguration, the Senate approved the appointment of Woodin as the Secretary of the Treasury. With his new Treasury Secretary in place, Woodin’s first act was to declare a three-day bank holiday in order to try to stop the failures.

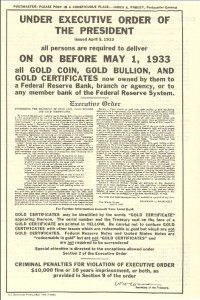

Handbill that was displayed in Post Offices calling for the recall of gold with the text of Executive Order 6102

Executive Order 6102 specifically exempted certain industrial uses of gold, art, and allowed people to keep up to $100 in face value in gold coins. It also exempted “gold coins having recognized special value to collectors of rare and unusual coins.” The protection of collectible coins was credited to Woodin since he was a collector of coins and patterns he acquired while director of the New York Federal Reserve Bank.

Although most of the country complied with the executive order, some challenged the law and started to sue the government to stop the gold recall. With the challenges mounting, on June 5, 1933, congress formally takes the United States off the gold standard by enacting a joint resolution (48 Stat. 112) nullifying the right of creditors to demand payment in gold.

For weeks after FDR issued EO 6102, the U.S. Mint continued strike gold double eagle coins because they did not have an order to stop. After receiving the stop work order, the coins were stored until they were ordered melted in 1934.

Even though the double eagles were melted, several examples of the 1933 Saint Gaudens double eagle gold coin did find its way out of the Mint. While most were tracked and confiscated, one example found its way to Egypt into the collection of King Farouk. This was the coin that eventually was sold in 2002 for $7,590,020 ($20 given to the government to monetize the coin) to a private collector. Half of the proceeds were paid to the government as part of a settlement with British coin dealer Stephen Fenton, who was arrested trying to sell the coin at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in 1998.

-

Reverse of the iconic 1933 Saint Gaudens

$20 Double Eagle gold coin

But that does not end the story of the 1933 Saint Gaudens double eagle. Since the sale of the only legal tender 1933 Double Eagle, ten coins found by the family of the late jeweler and coin dealer Israel Switt. The coins were sent to the U.S. Mint for authentication and were subsequently confiscated when they were determined to be genuine.

These coins are known as the “Langboard Hoard,” named for Joan Landbord, the daughter of Israel Switt, who claims to have found the coins while searching through her father’s old goods. On more than one occasion, Switt has been accused of being the source of the 1933 Double Eagle coins that made it out of the Philadelphia Mint.

In July 2011, a jury ruled that the 10 coins in the Langboard Hoard belong to the government. The case is currently being appealed.

The story of 1933 Saint Gaudens double eagle is truly an example of the law of unintended consequences. In an effort to rescue the economy, the cascading series of events that took the United States off the gold standard turned what was supposed to be an ordinary coin into one of the most intriguing stories of the 20th and now 21st century.

All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

If the goal was to stop gold from leaving the U.S., why couldn’t they pass a law making it illegal to export gold instead of criminalizing the ownership of gold by U.S. citizens? Besides most of the gold that left the U.S. over the years leading up to these events was exported by the U.S. government, for example to pay off war-time debts.