June 2020 Numismatic Legislation Review (a little late)

There is a meme going around the Interwebs that shows Doc Brown (Christopher Lloyd) getting out of his modified DeLorean with Marty McFly (Michael J. Fox) standing there with Brown telling Marty not to set the time machine to 2020. If you do not understand the meme, I recommend you stream Back to the Future on your favorite streaming platform. It is a classic movie!

There is a meme going around the Interwebs that shows Doc Brown (Christopher Lloyd) getting out of his modified DeLorean with Marty McFly (Michael J. Fox) standing there with Brown telling Marty not to set the time machine to 2020. If you do not understand the meme, I recommend you stream Back to the Future on your favorite streaming platform. It is a classic movie!

We are 13 days into July, and I realized that June was over, and the Legislative Update was due. Then again, we discussed the only legislation that Congres introduced in June. Otherwise, there is nothing to report on the legislation front.

S. 4006: Coin Metal Modification Authorization and Cost Savings Act of 2020

Stories That Sell

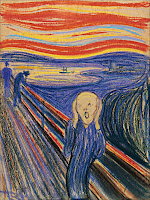

Earlier this week, “The Screem,” an iconic painting by Norwegian impressionism artist Edvard Munch was sold at auction [PDF] by the famous Sotheby’s auction house. The hammer price with auction premium was a record $119,922,500 to an anonymous buyer.

Earlier this week, “The Screem,” an iconic painting by Norwegian impressionism artist Edvard Munch was sold at auction [PDF] by the famous Sotheby’s auction house. The hammer price with auction premium was a record $119,922,500 to an anonymous buyer.

Classic works of iconic designs do very well at auction. In the numismatic world, Augustus Saint-Gaudens’ Liberty design is one of those iconic image. First appearing in 1909, it was used on all $20 Double Eagle coins struck until 1933. When the American Eagle bullion program was introduced, the design was returned to the American Gold Eagle coins.

Of the coins bearing the Saint-Gaudens design, the 1933 Double Eagle is the most iconic of the series. It was not supposed to exist. After two were sent to the Smithsonian Institute, the balance of the 445,500 mintage was supposed to have been destroyed as part of the gold recall ordered by Franklin D. Roosevelt at the beginning of his presidency. In a story that inspired two very good books, it was found that the only 1933 Double Eagle that is legally in private hands was once authorized to be exported to Egypt to be in King Farouk’s collection.

After many years of fighting, the auction by Sotheby’s-Stacks sold the coin to a private collector for $7,590,020 in 2002, with $20 being paid directly to the U.S. Treasury to monetize the coin. This remains the record for the sale of a single coin.

After many years of fighting, the auction by Sotheby’s-Stacks sold the coin to a private collector for $7,590,020 in 2002, with $20 being paid directly to the U.S. Treasury to monetize the coin. This remains the record for the sale of a single coin.

If a good story sells a coin, then the story of the 1933 Double Eagle will continue to drive up the price of the coin. Last July, a jury awarded ten 1933 Double Eagle coins owned by Joan Landbord to the government. Langbord, the daughter of Israel Switt, claims to have found the coins while searching through her father’s old goods. On more than one occasion, Switt has been accused of being the source of the 1933 Double Eagle coins that made it out of the Philadelphia Mint.

Although the coins remain locked up at the United States Bullion Depository in Fort Knox, Kentucky, the Langbord family is planning an appeal of the court’s decision. Even through there are three other known specimens, this story is going to drive up the price of these coins.

Stories can turn an average design into something spectacular. For instance, the 1913 Liberty Head Nickel does not have one of those iconic designs. In fact, President Theodore Roosevelt called the design by the Mint’s Chief Engraver Charles Barber “hideous.” But as an extension of Roosevelt’s “pet crime,” the coin was being replaced by the to-be-iconic Buffalo Nickel design by James Earle Fraser. But in 1913, Mint employee Samuel Brown allegedly had five examples of the Liberty Head design struck as souvenirs.

The story becomes more interesting with the pedigree of each coin. The Eliasberg Specimen once was a feature of the Louis Eliasberg collection, a Baltimore financier who attempted to collect an example of every known coin. This coin was sold in 2007 to a private collector for $5 million, currently the second most amount paid for a single coin.

The story becomes more interesting with the pedigree of each coin. The Eliasberg Specimen once was a feature of the Louis Eliasberg collection, a Baltimore financier who attempted to collect an example of every known coin. This coin was sold in 2007 to a private collector for $5 million, currently the second most amount paid for a single coin.

Other storied coins include the Olsen Specimen that was once owned by Egypt’s King Farouk and appeared on the first version of the television show Hawaii Five-0. The McDermott specimen is the only one that shows signs of circulation and is now part of the American Numismatic Association Money Museum’s collection. The Norweb Specimen is now part of the Smithsonian Institute’s National Numismatic Collection.

The Walton Specimen was once owned by dealer and collector George O. Walton who died in an automobile accident in 1962. In an attempt to auction the coin in 1963, it was thought to be one of the copies that Walton was known to carry around. For forty years, Walton’s daughter kept the coin in a box that was sitting in the bottom of a closet. The coin was brought to the 2003 ANA World’s Fair of Money in Baltimore where a group of experts spent hours authenticating the coin as genuine.

Recently, the 1792 Silver Center Cent, a pattern that was the first coin struck at the new Philadelphia Mint, sold for $1.15 million. Its design features the work of chief coiner Henry Voight, whose liberty head design has been described as “scary.” But it is the story of the founding of the Mint and of the Mint’s first director, David Rittenhouse.

Recently, the 1792 Silver Center Cent, a pattern that was the first coin struck at the new Philadelphia Mint, sold for $1.15 million. Its design features the work of chief coiner Henry Voight, whose liberty head design has been described as “scary.” But it is the story of the founding of the Mint and of the Mint’s first director, David Rittenhouse.

We may never see rare coins sell for the same prices as famous works of art, but the numismatic community can celebrate the stories and history of these iconic coins in a way that the art world is not able to, which makes numismatics a special hobby.

Image Credits

Image of The Scream courtesy of the Associated Press.

1933 Double Eagle image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Eliasberg 1913 Liberty Head Nickel image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Image of the 1792 Silver Center Cent Pattern courtesy of Heritage Auction Galleries.

The Canadian Penny: RIP

Dignitaries were present at the Royal Canadian Mint in Winnipeg to honor (or mourn) the striking of the last Canadian penny.

Dignitaries were present at the Royal Canadian Mint in Winnipeg to honor (or mourn) the striking of the last Canadian penny.

Citing its low buying power and that it costs 1.6 Canadian cents to produce one coin, Canadian Finance Minister Jim Flaherty announced in March that the government will end the coin’s production. Cash sales will be rounded up or down to the nearest 5-cents while non-cash transaction will continue to be settled to the nearest cent.

After a brief ceremony that included Flaherty and Ian E. Bennett, President and CEO of the Royal Canadian Mint, the last penny was struck and carried from the presses by Flaherty. It will be given to the Canadian Currency Museum located within the Bank of Canada complex in downtown Ottawa for display

Ceremony images from the Royal Canadian Mint via Twitter.

Cent coin image courtesy of the Royal Canadian Mint.

History of Currency and Collecting Currency

Paper currency was first developed in China in the 7th century and later adapted by the Mongol Empire before spreading to Europe and then the United States. China developed currency because of a shortage or metals. Notes printed promised the holder that it be redeemed for something of value and can be traded as specie. The Mongolian Empire learned from the Chinese and issued currency that they backed by the assets of their conquests. Since both China and Mongolia issued state guaranteed currency, the paper was trusted in commerce and helped build a steady stream of commerce between Europe and the east.

Although Europe traded eastern currency as trade was opened between the regions, currency was not a part of regular trade until the 13th century. In Europe, individual banks issued currency as a promissory note against assets held by the bank. Essentially, these were promissory or demand notes that was supposed to allow the holder to trade the note for specie on demand. Unfortunately, the practice was abused to try to raise additional capital and caused a lot of banks to fail.

The problem was not limited to private banks or loan companies. Banks owned by the nation states also tried to use currency as an investment vehicle without sufficient funds to back their values. Currency manipulation by those banks lead to man bank failures and economic depression that are woven through some of the strife through Europe.

Switzerland, France, and England were the first counties to organize and regulate the banks and regulate how they issue currency. Each country has experienced bank failures of not only the state chartered banks but the state central bank making the issued paper currency worthless.

Currency did not see a wide acceptance until it was issued in the Massachusetts Bay Colony in the 17th century. It was the first time that currency was issued in predetermined amounts. Since the colonies did not have the ability to coin money, all colonies issued its own currency by the 18th century. These notes functioned as currency but actually were bills of credit, short-term public loans to the government. For the first time, the money had no intrinsic value but was valued at the rate issued by the government of the colony in payment of debt. Every time the colonial government would need money, they would authorize the printing of a specified quantity and denomination of notes that it would use to pay creditors. The emission laws also included a tax that would used to repay the bill of credit and the promised interest.

As taxes were paid using the paper currency, the paper was retired. As the notes were removed from circulation, that was less payments the government had to make. On the maturity date, people brought their notes to authorized agents who paid off the loan. Agents then turned the notes over to the colonial government to be reimbursed and collect a commission for acting as an agent.

Sometimes, colonies could not pay back the loan. In those cases, the colonies passed another emission law to cover the debt owed from the previous emission plus further operating expenses. In this case, mature notes were traded for new notes. The colonists accepted this system since there were shortages of coins as well as there being an inability to convert the value of foreign coins into colonial shillings by farmers and other unskilled in such matters.

During the revolutionary war, the Continental Congress began to issue paper money to support the war efforts. The colonies also continued to issue paper currency. While the colonial issued notes had some value, those issued by the Continental Congress was not as sure and the notes’ value plummeted. With the saying “Not Worth a Continental” becoming popular so did the term “shinplasters” to describe the notes lining colonialist’s boots to help keep their feet warm.

Counterfeiting was rampant by the mid-18th century. In order to combat the problem, Benjamin Franklin devised the nature print, an imprint of a leaf or other natural item with its unpredictable patterns, fine lines, and complex details made it more difficult to copy.

To create a nature print, Franklin placed a leaf on a damp cloth. The cloth was placed on top of a bed of soft plaster that pressed the leaf into the plaster. Once the plaster hardened, it had a negative impression of the leaf. Molten copper was then poured over the plaster to make the printing plate. Franklin first used nature prints for the 1737 New Jersey emission. He also used different leaves for different denominations and elaborately engraved borders to further thwart the efforts of potential counterfeiters.

Franklin partnered with David Hall printing notes for New Jersey and Pennsylvania colonies. Along with his nature print, Franklin also included the phrase “Tis Death to Counterfeit.” Aside from trying to scare away potential counterfeiters, the penalty for counterfeiting in the 18th century was death. No convictions for counterfeiting colonial currency or death sentences have been recorded.

Later, Hall partnered with William Sellers to print Pennsylvania currency when the Pennsylvania assembly sent Franklin to England as their colonial agent.

Other printers tried different methods to thwart counterfeiters. James Parker of Woodbridge, New Jersey printed notes in two colors. With printing a labor-intensive process, it was thought the process to cumbersome for counterfeiters to go through the process of the second printing. Also, Parker used red ink as the second color. Red was more expensive than black ink in the 18th century.

The next wave of note is known as Obsolete Notes, sometimes called Broken Banknotes. These were privately issued currency starting in the 1830s backed by the assets of the issuing bank. These notes became obsolete in the 1860s when many of the issuing banks failed and the federal government changed the laws regarding currency issues. Obsolete notes are a popular collectible since many feature beautiful images, called vignettes, that represent local industries or patriotic themes.

As the Civil War raged, the public hoarded coins creating a shortage of circulating coinage. People started to use postage stamps for transaction requiring small change. Stamps were traded in envelopes that would fall apart causing the gum on the back to make them a sticky mess. As a result, the post office issued small, rectangular Postage Currency in 1862. Postage currency was larger than the postage stamp without the gum on the reverse, and the front depicted the postage stamp and its value. Without the adhesive, they could not be used for postage but could be redeemed at any post office for its face value.

Currency in the United States went from its chaotic stage to something the government issued and regulated with the passage of the National Bank Act of 1863. The law replaced the postage currency with fractional currency. Authorize by the government and printed by the American Banknote Company, fractional currency was issued through 1876 when coinage production caught up with demand and hoarding had ended. At this time, the Currency Bureau, later to be renamed the Bureau of Engraving and Printing (BEP) was created to cut and distribute the notes. Fractional currency is a popular collectible especially amongst those with interest in the Civil War.

Another Civil War collectible is Confederate Currency. These banknotes were primarily demand or promissory notes back by non-existent assets that made the notes worthless by the end of the war. During the war, the Confederate States of America issued seven series of currency printed by different printers throughout the south, some in the north, and in London. Confederate coinage, also collectible, was struck using mints under siege in Charlotte, Dahlonega, and New Orleans. During the Civil War, the chief coiner of the New Orleans Mint fled to France to continue producing coins for the Confederacy. This history makes these numismatics are very collectible by history and Civil War buffs.

Following the Civil War, paper currency is identified by type, denomination, and series date. The series date is not necessarily the date in which the note was issued. The series could represent the year the law authorized the notes, the year the production began, or in the case of current Federal Reserve Notes, the year when the signature of the Secretary of the Treasury changes.

Not including fractional and Confederate currency, the following are characteristics of United States currency:

- Demand Notes were the first paper currency printed for the United States government for general circulation. These notes were essentially loans to the government during the Civil War to be paid on demand at designated Treasury offices following a maturity date. The backs of these notes were printed in green to prevent counterfeiting by people taking pictures of the note using a camera, the new technology of the time. Green did not photograph well. The term “greenback” came from the use of green inks to print these notes.

- United States Notes were the first currency authorized by the Legal Tender Act of 1862 and the first notes printed by the National Currency Bureau. Also known as Legal Tender Notes, these notes were supposed to be backed by assets held by the government that were not necessarily precious metals. Large size United States Notes are very collectible with great designs that make them special.

- National Bank Notes allowed banks with a federal charter to issue notes against their assets. In order for the banks to be allowed to issue currency, they had to purchase bonds from the Treasury and were allowed to issue currency up to 90-percent of the value of those bonds. The bonds were used by the federal government to insure the value of the notes. All notes were printed by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing to ensure that the designs were identical with only the bank name, location, and charter number printed for the issuing banks. The National Bank Note program ended in 1935 when the bonds securing the notes were terminated as part of the banking reorganization during the Great Depression. National Bank Notes are great collectibles for those interested in collecting items representing a state or region.

- Silver Certificates began in 1878 when the government decided to increase the production of silver coinage with the passage of the Bland-Allison Act to satisfy silver mining interests. Silver coins were deposited with the Treasury and the equivalent dollar amount of silver certificates where produced. Silver Certificates could have been presented to the Treasury Department and redeemed for silver dollars. The series 1953B silver certificates were the last produced for circulation. In 1964, with the price of silver rising, the Treasury stopped redeeming silver certificates for silver dollars and started to distribute small vials of silver flake equal to $1. This redemption program stopped in 1968. All but the very rare 1934 Yellow Seal North Africa notes are available for collectors in nearly every denomination.

- Gold Certificates were generally used to transfer money between banks and other large financial institutions. First issued in 1878, Gold Certificates were backed with gold deposited with the Treasury. Some of the lower denominations did circulate to a limited degree, but banks used others. Gold certificates were printed with bright colors, mostly gold-colored, and the reverse on the large notes (pre-1929) were also gold-colored. Small notes were printed with the traditional green reverses. Gold certificates were recalled with the gold recall in 1933.

- Treasury Notes were issued as part of an 1890 and 1891 series to be paid to individuals selling silver bullion to the Treasury. Those paid with these notes could redeem them for the equivalent value in gold coins. The Treasury stopped this program after 10 years because of the considerable amount of labor required to carry out this program.

- Federal Reserve Notes (FRN) were first issued in 1914 by the newly formed Federal Reserve System and are still being printed and distributed today. When first issued, FRNs were printed as large size notes and were reduced to the small notes we are used to today in 1929. After 1945, the Bureau of Engraving and Printing stopped printing all denomination over $100. By 1969, those large denominations were removed from circulation. Designs of FRNs remained the same until 1995 when the BEP altered the designs to include new security features. However, the $1 FRN has not changed since it was first introduced in 1929. FRN are readily available and accessible to most collectors. Common ways of collecting is by signature pairs. Other ways of collecting FRNs is by serial number patterns (e.g., radar patterns, series, low numbers, etc.), and by Federal Reserve District represented by the note.

- Federal Reserve Bank Notes (FRBN) began to be issued in 1915 to transition from National Bank Notes to Federal Reserve notes. FRBN were obligations of the issuing Federal Reserve Bank branch and not the U.S. government. FRBN production was discontinued in 1934 and were stopped being issued in 1945. Since FRBN resembled National Bank Notes except that the issuing bank is a Federal Reserve Branch and are printed with “National Currency” across the top.

Currency collections can be as varied as the types of currency printed. Some currency was printed with themes such as the Educational Series of 1896 that used allegorical images in an attempt to educate the public. Other ways to collect currency is by their design, the color of the seal, the issuing bank, serial numbers, and signers.

If you collect by signers on the note, one of the more interesting notes is known as Barr Notes named for Joseph W. Barr, the 59th Secretary of the Treasury. Barr was confirmed and sworn into office on December 21, 1968, one month before the end of the Lyndon B. Johnson administration. Since the Secretary of the Treasury’s signature is on all Federal Reserve Notes, the BEP printed over 485 million one dollar notes with Barr’s signature before his term ended on January 20, 1969.

In the case of currency, size matters. Aside from the denomination, standard currency printed by the BEP used to be larger than it is today. Prior to 1929, U.S currency was 7 1/2 inches long by 3 1/8 inches wide. These are commonly called large notes. Another nickname for these notes are horse blankets. Beginning in 1929 with the Series 1928 notes, U.S. currency was reduced to the 6 1/8 inches by 2 5/8 inches notes we are used to using today. These are commonly called small notes.

If you ever looked at a note and noticed that a star (“*”) was included in the beginning or end of the serial number, you have a Star Note. A Star Note is used to denote that the note is a replacement note for one found to be defective or damaged during the printing process. To maintain the correct number of notes in a print run, the serial numbers are reclaimed and a star is added to note the replacement. Since Star Notes are replacements for errors, they are not as common as normal notes and are popular with collectors.

SF Mint 75th Anniversary Eagles

The San Francisco Branch of the U.S. Mint first opened in 1857 to serve the coinage needs caused by the California Gold Rush. With the population growth in California and the demand for coins the Mint out grew the building and built a new Mint that was opened in 1874.

The new building was built beyond specification to be secure based on the known risks of the times. One worry about the new building was preventing the ability for someone to break into the building by tunneling into the basement. To prevent this, the foundation and basement were made with granite. Although the above ground structure was built using sandstone, the building earned the title “Granite Lady” following the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake when it survived with only a few exterior cracks.

The Granite Lady was the only building in its area to survive the destructive force of the quake. After the earthquake, the Mint Superintendent Frank Leach and his staff used the building and the grounds to assist with the rescue and housing effort after the earthquake. A tent city was built around the Mint and stayed until there were places for them to move.

Production continued with coins bearing the familiar “S” mintmark. Amongst the coins struck at The Granite Lady is the famous 1909-S VDB Lincoln Cent. The year after producing only 309,000 1908-S Indian Head Cents, the San Francisco Mint geared up to increase the production of the newly introduced Lincoln Cent. As the new coins landed in circulation, there was an outcry over the large “V.D.B” initials on the reverse for designer Victor David Brenner, the Mint stopped production of the coins. The Mint in San Francisco stopped after production of 484,000 of these cents, making it one of the most desired collectibles and a key date in the Lincoln Cent series.

As what happened after the San Francisco Branch Mint opened, they began to outgrow The Granite Lady. At the same time that congress authorized $524,000 to build the Bullion Repository at Fort Knox in 1935, they authorized $1.225 million to build the new San Francisco Mint.

The state of the art facility was built as a fortress with two-foot reinforced concrete walls to protect the vaults, a pistol range on the fifth floor, and tear gas pipes throughout the building for security. Also included in the construction was a generator to operate the electricity in case the power was cut to the building. When it opened, there was a plumbing shop, carpentry shop, and a blacksmith shop to support operations.

San Francisco’s new Mint opened in 1937 and became fully operational by 1938. It continued to strike circulating coins until 1955. In 1962, San Francisco was “downgraded” to an assay office. As an assay office, it struck circulating coinage starting in 1968 and ending in 1974. The San Francisco facility continued to strike proof coinage and added striking circulating Susan B. Anthony Dollars from 1979 through 1981.

Since 1981, the San Francisco Mint has struck Lincoln Cents for circulation to supplement the output of the Philadelphia Mint. It is not known how many cents San Francisco produced since their coins contained no mint mark and their inventory was included in the general reporting by the U.S. Mint without distinguishing between the facilities.

The San Francisco Assay Office was officially granted mint status again on March 31, 1988 as part of Public Law No. 100-274. That law also granted mint status to Silver Bullion Depository at West Point.

To celebrate the 75th Anniversary of the “new” San Francisco Mint, the U.S. Mint will sell a two-coin American Silver Eagle Proof set struck at the San Francisco Mint featuring the “S” mintmark. The set will include one regular proof and one reverse proof coin in a special presentation case.

In an attempt to avoid the problems of the past, the U.S. Mint will take pre-orders for the set and strike as many as collectors purchase. The U.S. Mint is likely to limit the number of sets sold during the pre-sale period, but there will be no limits on the number of sets produced.

The San Francisco Mint will begin to strike American Silver Eagle Proof coins on May 11 and will host a public ceremony on May 15. This set be on sale only during the period of June 7, 2012, to July 5, 2012 with mintage limits is being reported as “to demand.” Price has yet to be announced.

The American Silver Eagle Reverse Proof has to be one of the best looking coins produced by the U.S. Mint in the last 50 years. Aside from using the Adolf A. Weinman Walking Liberty design, which is one of my favorites, the shiny relief over the matte field really makes the design pop.

With the current American Silver Eagle Proof coin selling for $59.95, it is possible that the San Francisco set would be priced around $120. However, I think the set price may be set to $99.95 to increase sales and show some good will to collectors, especially those that were shutout of purchasing the 25th Anniversary Silver Eagle Set.

As an aside, the 100,000 unit 25th Anniversary set sold for $299.95. Recent price guides show that the set is selling is worth $825. Since the U.S. Mint plans to strike “to demand,” it is unlikely the San Francisco Anniversary set will see that kind of increase on the secondary market.

Image of the San Francisco Mint after the 1906 Earthquake courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Image of the new San Francisco Mint courtesy of Wikipedia.

Image of the San Francisco 75th Anniversary Silver Eagle Set courtesy of the U.S. Mint.

History of Coin Collecting

Numismatics is the collecting and study of items used in the exchange for goods, resolve debts, and objects used to represent something of monetary value. The dominant area of numismatics is the collection and study of legal tender coins with United States coins being the most collected. But there are so many other forms of numismatics that there are collectibles to pique anyone’s interest.

Evidence of coin collecting has been found as far back to the early days of the Roman Empire when collecting art came into vogue. Since coin design was considered art, it was assumed that coins were part of every collection. Archeologists have discovered hoards of coins with no two being alike in the areas believed to be cultural centers of the Roman Empire. The fact that the hoards have unique coins have archeologist beliving that these were lost collections.

Coin collecting did not become a broader hobby until the Italian Rennaisance when the lords and kings began to collect what we call ancient coins primarily found on their land or during conquests of other lands. Since only these nobles could afford to collect, coin collecting became known as the “Hobby of Kings.”

By the 17th century, collectors started to study and catalog the coins in their collection beginning the era of numismatic research that continues today. As the study of the coins began to advance, there was the rise of public collections. Coins held by the royalty were either given or confiscated for the state and placed in museums. As the collections began to build, museums began to sponsor research to document their holdings.

Modern numsimatics is said to have begun in the 19th century with the interest in the coins of a new nation. Collectors in the United States and overseas saw potential in the promise of the new coinage as the nation grew. By the latter part of the century after congress ended the use of foreign coins in commerce, collectors started to hoard older designs and created clubs for collectors to network and share information.

The 20th century saw new markets for numismatics develop. Growing interest in numismatics caused excavation of sites believed to have been inhabited in ancient times to find coins while hoards of United States gold and silver coins were being discovered primarily in Europe with others found in Asia. Collectors started searching banks and pocket chains for coins like the 1909-S VDB and 1914-D Lincoln Cents, 1913 Type 1 Buffalo Nickels, and 1916-D Mercury Dime.

The first change in numismatics came with the introduction of the coin board, cardboard-made boards with holes the size of the coins so that collectors can organize their collections. Coin boards introduced the concept of collecting coins in a series. Boards were printed to allow the collector to insert coins of each date and the date with mint mark. Soon after publishers printed folders that brought down the size of the coin board so it could fit on a book shelf and then the album with the ability to view both sides of the coin.

Another change occurred in 1955 when the 1955 Double-Die Obverse (DDO) Lincoln Cent was discovered. Known as the “King of Errors,” this coin lead to collectors to search for errors, varieties, and anything out of the ordinary. New clubs were formed to organize and promote this new hobby segment. One of the most comprehensive study of die varieties was published in 1971 by Leroy C. Van Allen and A. George Mallis. Their book, The Comprehensive Catalog and Encyclopedia of Morgan & Peace Dollars, documents the dies and strike varieties of America’s last circulating large silver dollars. Their catalog, also known as the “VAM Book” provides a numbering system to identified the different varieties whose impact created a new way to collect silver dollars.

The biggest change in coin collecting occurred in 1965 when the United States stopped striking coins using silver. With the price of silver rising and costing more than their face value, the country was facing a coinage shortage as people started to hoard the coins vor their silver values. Although the government erroneously blamed collectors, congress voted to change the composition of what were silver coins to copper-nickel clad alloy. Even though the half-dollar continued to be minted in silver until 1970, the silver was clad over a copper core.

Collectors consider 1964 the end of the United States’s classic coin era and 1965 the beginning of the modern era. The modern era saw the last of the large dollars and the transition to the small dollars, changes in composition for the Lincoln cent, the rotating circulating commemorative series beginning with tht 50 State Quarters program, and the reintroduction of the commemorative coin program. Another addition to the modern era in the United States and around the world is the resurgance of bullion coins.

After the world stopped using precious metals for coins, South Africa made a strategic decision to continue to strike the 22-karat krugerrand for world investment. For many years, the krugerrand was the standard for bullion investment until the United States began the American Eagle Bullion Program striking silver and gold coins. While other countries have followed suit, the American Eagle set the standard that other countries followed. Also popular at the Chinese Pandas, Canadian Maple Leafs, British Britannias, Mexican Libertads, and Australia Kookaburra.

Bullion programs lead to a new set of collectibles that are a cross between bullion and commemoratives called non-circulating legal tender (NCLT) coins. NCLT collecting has introduced new collecting opportunities by allowing mints and central banks to create new themes to intice new collectors and established collectors to expand their collections with new coins.

Rotating circulating commemorative designs and NCLT coins along with an expanded interest in other numismatic collectibles from the past including obsolete tokens, medals, old stock certificates, and paper money gives the numismatic collector an opportunity to create great collectings by collecting what you like.