Dec 30, 2011 | history, news

Why do you collect? Around here we collect coins, currency, exonumia, and other forms of numismatics. In addition to coins, I collect post cards with subjects that are meaningful to me—such as the little village on Long Island where I first grew up. I also collect lapel pins that I have either picked up over the years or have some other meaning to me. For me, my collection has a meaning to me, including the set to New York City Subway tokens.

Those of us who are collectors knows that along with the thrill of the chase, there are times when we can take it too far. When does it become too much?

The New York Times opinion section, Room for Debate, asked seven experts in various areas of collecting to try to answer these questions. One of the experts that were invited to write a short item for the December 30th discussion, “Why We Collect Stuff” is your favorite blog host.

Besides, if you are curious as to what I look like, there is a current picture (a head shot taken last Sunday) associated with the article.

All of the articles are well written and add value to the discussion about collecting and hoarding. I invite my readers to read the discussion. You can either comment on The New York Times website or you can return here—or both!

Sep 25, 2011 | cents, errors, history

In the world of collecting, collecting coins with errors is a relatively new specialty. The specialty can be traced to the discovery of the famous 1955 Lincoln Cent Doubled Die Obverse (DDO), known as The King of Errors. Finding this coin lead to collectors to search for errors, varieties, and anything out of the ordinary.

In the world of collecting, collecting coins with errors is a relatively new specialty. The specialty can be traced to the discovery of the famous 1955 Lincoln Cent Doubled Die Obverse (DDO), known as The King of Errors. Finding this coin lead to collectors to search for errors, varieties, and anything out of the ordinary.

What is a “Doubled Die?”

In order to strike coins, the U.S. Mint creates dies from hubs that contain the engraved image of the coins. The hubs are pressed into the dies to transfer the image. In years past, the U.S. Mint used to use what they called a two-squeeze process to make sure the die had a full image. This meant that when pressing the hubs into the dies, the die makers squeezed the two parts twice.

Sometimes, the process does not go smoothly and mistakes are embedded in the dies. In the case of the 1955 DDO Lincoln Cent, the hub and die did not line up correctly on the second squeeze. The result was lettering that appeared shifted or doubled.

Initial Reaction to the Coin

When the coin was discovered, there were two reactions. One group of people saw the coin as an exciting find and wondered whether it happened on any other coins. Another group was not as happy. They referred to the coin as “spoiled” and refused to acknowledge it as a valid collectible. Some considered the coin so unremarkable that one club publication wrote how they were having a hard time selling the coins for one dollar each.

A New Hobby Segment is Born

Those who were excited by the new find began to form clubs dedicated to the finding and education of errors and other variety in U.S. coins. They started the Collectors of Mint Errors (COME) club in 1956. As the nascent club tried to find its footing in the hobby, two factions began to form around different error and variety types. COME disbanded in 1960 because of the in fighting between the two organizations.

Some former members of COME came together again in 1963 to form the Collectors of Numismatic Errors (CONE). The people who formed CONE focused mostly on die varieties such as doubled dies, repunched mintmarks, major die breaks, die cracks, and die chips. Other collectors who were more interested in major minting errors like the 1955 DDO Lincoln Cent formed the Numismatic Error Collectors of America (NECA).

The two clubs existed for many years as rivals believing their form of collecting errors was better than the other. During this time, both clubs provided a lot of research into errors and varieties and how they could have occurred. The publications from both clubs continue to be the basis of the knowledge still used today.

Combining Forces

In 1980, the two organizations began to find common ground and discovered that it was better to work together than against each other. As the two clubs started to work together, many collectors became members of both clubs. To strengthen the hobby, both clubs voted to merge in 1983 to form the Combined Organizations of Numismatic Error Collectors of America (CONECA).

Finding Errors and Varieties

Today you can find error coins at your local coin store or by contacting a dealer specializing in errors and varieties. CONECA members will tell you that the thrill of finding errors is in the hunt. Error collectors use magnifying loupes, a good light source, and a lot of patience to examine coins to find something out of the ordinary. While there are some errors that are as visible as the 1955 DDO Lincoln Cent, others can be as subtle as outline of a small crack in the die, imperfections caused by two dies striking because the machine did not place a blank planchet properly between the dies, or the wrong die was used to strike the coin.

Errors can be found on any type of coin from any era. The error collecting community became excited when the processing of the new Presidential Dollars did not include the edge lettering; the edge letters were not aligned properly or doubled. While the U.S. Mint has improved the minting process, error collectors continue to find errors every time new coins are issued.

Starting an Error Collection

Anyone who wants to start searching for errors and varieties might want to buy a copy of Strike It Rich With Pocket Change by Brian Allen and Ken Potter published by Krause Publications (e-reader versions available). Now in its third edition, Strike it Rich will show you what to look for when you examine the coins in your pocket. According to the authors, a collector found a double die cast 1969 Lincoln cent in a roll of coins. When it was auctioned in 2008, it sold for $126,500.

Another great resource is Cherrypicker’s Guide by Bill Fivas and J.T. Stanton published by Whitman Publications. The fifth edition published in 2008 has more pictures, better descriptions, and a more complete resource with additional prices realized from various auction sources. A new edition is due later this year and should be available in e-reader formats.

Do not forget the resources of CONECA, which could be found on their website at conecaonline.org.

The 1955 DDO Lincoln Cent Today

As a coin desired by all types of collectors, a mid-grade coin you could have bought for $1 in 1960 is worth around $1,500 today. It is a coin that has held its value even during the current economic downturn but has not seen significant appreciation in the last ten years. Collectors will be happy the one they own will maintain its value. Investors should look to the highest graded coins that are designated as Red (full mint luster) or Red-Brown (some light copper oxidation) for better future returns.

Sep 12, 2011 | history, nickels

My earliest memory of learning about Theodore Roosevelt was going with the Cub Scouts to visit Sagamore Hill, his estate in Oyster Bay, New York. Roaming through Sagamore Hill with my fellow Scouts brought fascinating images of Roosevelt’s trophies from his various hunts. The skins, heads, and an ashtray made from an elephant’s hoof made quite an impression on this group of 7-8 year olds.

A special memory was of the bathrooms. Aside from looking very primitive compared to what we have in our homes even in the mid-1960s, but our Cub Master, who was also my best friend’s father, was a plumber. At times, he was worked for New York City as a plumbing inspector. We had fun poking fun at him using the facilities at Sagamore Hill as a background!

When I learned more about United States history in high school, I read more about the life and presidency of Teddy Roosevelt. I was impressed with his background of working through his health issues, was fascinated to read of his life in the Badlands in South Dakota, and interested to read about his political life as someone who demonstrated a great regard for the law and someone who wanted to make things better. Although I was not as physical as Roosevelt, his principled stance made an impression on me.

Before returning to collecting, I read The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt by Edmund Morris. It was not the easiest read because Morris used the late Victorian writing style that was popular during Roosevelt’s life. Once I became used to the style, Morris brings the reader along with Roosevelt into the mud of the Badlands, the halls of the New York legislature, as one of the police chiefs of New York City, Governor of New York, Secretary of the Navy, and Vice President. Through Morris’s words, it was like riding that freight train what was Theodore Roosevelt.

I returned to collecting in 2001 following the death of my first wife. During a particular spending spree, I bought Morris’s second volume, Theodore Rex. Although I never finished this book—only because of timing—my interest in Roosevelt continued to grow.

Then I learned about Roosevelt’s “Pet Crime.” I learned how Roosevelt conspired with Augustus Saint Gaudens to improve U.S. coin design. I learned how Roosevelt was influenced by immigrant Victor David Brenner to have the U.S. Mint issue the Lincoln Cent. I learned how the seeds of his “Pet Crime” lead to what has been called a renaissance of U.S. coinage.

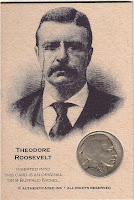

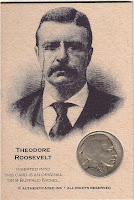

To say I am a sucker for Theodore Roosevelt memorabilia would be an understatement. Although I do not have many pieces, finding cool items is always a thrill. Imagine how my eyes lit up when I found a Theodore Roosevelt card with a 1919 Buffalo Nickel. I did not know much about it, but I had to buy it. The final cost was not that expensive, but it was so cool that I did not care.

To say I am a sucker for Theodore Roosevelt memorabilia would be an understatement. Although I do not have many pieces, finding cool items is always a thrill. Imagine how my eyes lit up when I found a Theodore Roosevelt card with a 1919 Buffalo Nickel. I did not know much about it, but I had to buy it. The final cost was not that expensive, but it was so cool that I did not care.

When the card arrived, I was a little disappointed in that the card was modern and the nickel was very worn. I can change the nickel since 1919 Buffaloes are not that expensive. But I had to find out more about the card.

After asking around, I found that the company, Authenticated Ink, is an autograph collecting company that issued these cards in 2008 as a promotion. Authenticated Ink printed cards of sports and historical figures that included coins from the era of the person depicted on the card. I have had problems contacting Authenticated Ink (emails have not been returned), but sources tell me that there were not many of these cards issued.

It is a very cool collectible and has been added to my “oh neat” collection.

Sep 11, 2011 | commemorative, history

For those of us who lived through these events, the only marker we’ll ever need is the tick of a clock at the 46th minute of the eighth hour of the 11th day.

For those of us who lived through these events, the only marker we’ll ever need is the tick of a clock at the 46th minute of the eighth hour of the 11th day.

—President George W. Bush

Thousands of lives were suddenly ended by evil, despicable acts of terror. The pictures of airplanes flying into buildings, fires burning, huge structures collapsing, have filled us with disbelief, terrible sadness and a quiet, unyielding anger.

—President George W. Bush

Our enemies have made the mistake that America’s enemies always make. They saw liberty and thought they saw weakness. And now, they see defeat.

—President George W. Bush

The attacks of September 11th were intended to break our spirit. Instead we have emerged stronger and more unified. We feel renewed devotion to the principles of political, economic and religious freedom, the rule of law and respect for human life. We are more determined than ever to live our lives in freedom.

—Mayor Rudolph W. Giuliani,

December 31, 2001

Now, we have inscribed a new memory alongside those others. It’s a memory of tragedy and shock, of loss and mourning. But not only of loss and mourning. It’s also a memory of bravery and self-sacrifice, and the love that lays down its life for a friend–even a friend whose name it never knew.”

—President George W. Bush, December 11, 2001

This is a day when all Americans from every walk of life unite in our resolve for justice and peace. America has stood down enemies before, and we will do so this time. None of us will ever forget this day. Yet, we go forward to defend freedom and all that is good and just in our world. Thank you. Good night, and God bless America.

—President George W. Bush, September 11, 2001

$10 from the sale of every 9/11 Commemorative Medal goes to the National September 11 Memorial & Museum.

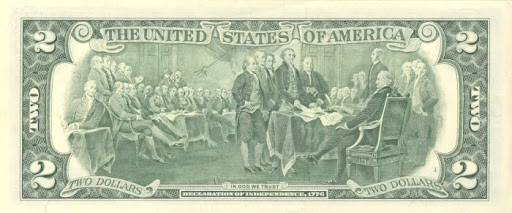

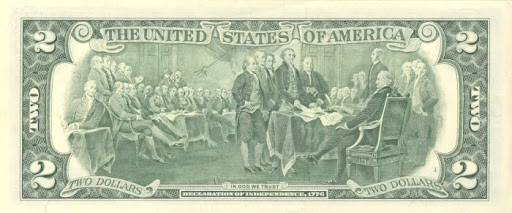

Jul 4, 2011 | history

In CONGRESS, July 4, 1776

The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America

When in the Course of human events it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.

When in the Course of human events it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. — That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, —  That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shewn that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security.

That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shewn that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security.

In every stage of these Oppressions We have Petitioned for Redress in the most humble terms: Our repeated Petitions have been answered only by repeated injury. A Prince whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the ruler of a free people.

In every stage of these Oppressions We have Petitioned for Redress in the most humble terms: Our repeated Petitions have been answered only by repeated injury. A Prince whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the ruler of a free people.

We, therefore, the Representatives of the united States of America, in General Congress, Assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions, do, in the Name, and by Authority of the good People of these Colonies, solemnly publish and declare, That these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States; that they are Absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved; and that as Free and Independent States, they have full Power to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do. And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor.

Adams Dollar image courtesy of the U.S. Mint.

Franklin Half image courtesy of PCGS.

Two Dollar reverse and John Hancock signature images courtesy of WikiMedia.

NOTE: The section containing the declaration of charges against King George III was intentionally omitted.

Jun 3, 2011 | currency, history

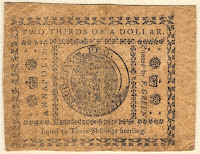

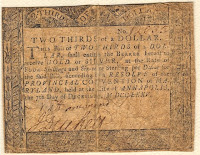

At the start of the Revolution, the Continental Congress allowed the colonies to print their own currency to help pay for the war. The Maryland Assembly approved an issue of $266,666 to be redeemed in gold or silver at 4/6 sterling per dollar by January 1, 1786. Backed by £100,000 still on account at the Bank of England, the emission was used to promote the manufacture of gunpowder.

To continue to pay for the war, the Maryland Assembly approved an emission of $535,111. The notes were to be payable by January 1, 1786 in gold or silver at the rate of 4/6 sterling per Continental dollar. Frederick Green printed these notes using new copper plates engraved in Philadelphia. The back depicted an arm holding a shield with the hand clenching the strap of the shield and holding a victory laurel with the motto SUB CLYPEO (Behind the shield).

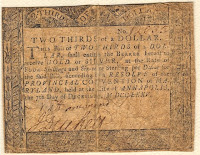

My new purchase in my Maryland Colonial series is a Two-Thirds Dollar note that was valued in 1775 as worth 3 Shillings Sterling. Because of the emergency nature of this emission, there were many signers of these notes. This PCGS Fine 12 example was signed by Nicholas Harwood and John Duckett. John Duckett, Jr. was the clerk in the lower house of the Colonial Assembly, Prince George’s County clerk, and distributor of currency on the western shore. Nicholas Harwood was Associate Clerk of the Court in Anne Arundel County from 1772–77 and later became Clerk of the same from 1777–1810. Harwood was a delegate to Maryland’s Constitutional Convention of 1776.

May 30, 2011 | commemorative, history

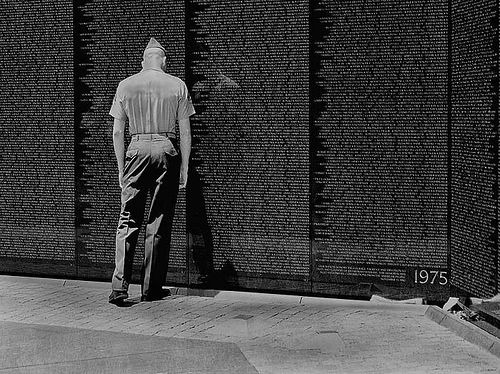

The first recorded organized public recognition of the war dead occurred on May 1, 1865 in Charleston, South Carolina. On that day, Freedmen (freed southern slaves) celebrated the service of the 257 Union soldiers buried at the Washington Race Course (now Hampton Park). They labeled the gravesite “Martyrs of the Race Course.” African Americans continued that tradition and named the celebration Decoration Day.

The next year, southern states began their own Memorial Days to honor their soldiers who died during the war. No specific date was used but occurred in late April through June. By 1880, there was a more organized Confederate Memorial Day. These celebrations honored specific soldiers to commemorate the Confederate “Lost Cause.” By 1913, a sense of nationalism saw a commemoration of all soldiers that have died in battle.

The next year, southern states began their own Memorial Days to honor their soldiers who died during the war. No specific date was used but occurred in late April through June. By 1880, there was a more organized Confederate Memorial Day. These celebrations honored specific soldiers to commemorate the Confederate “Lost Cause.” By 1913, a sense of nationalism saw a commemoration of all soldiers that have died in battle.

In the north, the fraternal organization of Civil War veterans The Grand Army of the Republic began organizing “Decoration Day” in 1868. Decoration Day was to honor the fallen by decorating the graves of Union soldiers with flowers and flags. Ceremonies included speeches that were a mix of religion, nationalism, and a rehash of history in vitriolic terms against the Southern soldiers. The acrimony against the South began to subside by the end of the 1870s

Although Ironton, Ohio and Columbus, Mississippi claims to have the oldest and longest running celebrations, the most famous was started at Gettysburg National Park in 1868.

Gettysburg is the location of the three day battle where Union Major General George Gordon Meade’s Army of the Potomac defeated attacks by Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. It was the bloodiest battle of the Civil War and had the largest number of casualties. During a 50th Anniversary memoriam of the deceased, veteran of the Union and Confederate armies gathered for a four-day “Blue-Gray Reunion.” The event included speeches by President Woodrow Wilson, the first southern elected president since the Civil War, and Congressman James T. Heflin of Alabama. Heflin’s speech was memorable in his endorsement of building the Lincoln Memorial and a call for a Mother’s Day holiday.

Gettysburg is the location of the three day battle where Union Major General George Gordon Meade’s Army of the Potomac defeated attacks by Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. It was the bloodiest battle of the Civil War and had the largest number of casualties. During a 50th Anniversary memoriam of the deceased, veteran of the Union and Confederate armies gathered for a four-day “Blue-Gray Reunion.” The event included speeches by President Woodrow Wilson, the first southern elected president since the Civil War, and Congressman James T. Heflin of Alabama. Heflin’s speech was memorable in his endorsement of building the Lincoln Memorial and a call for a Mother’s Day holiday.

Memorial Day did not take on national significances until after World War I. Rather than being a holiday to remember those of died in service during the Civil War, the nation began to recognize all those who gave the ultimate sacrifice during all conflicts. By the end of World War II, most of the celebrations were renamed from Decoration Day to Memorial Day. Memorial Day did not become an official holiday until 1967 and its date changed from the traditional May 30 to the last Monday of the month by the Uniform Holidays Act (Public Law 90-363, 5 U.S.C. § 6103(a)) in 1968.

Memorial Day did not take on national significances until after World War I. Rather than being a holiday to remember those of died in service during the Civil War, the nation began to recognize all those who gave the ultimate sacrifice during all conflicts. By the end of World War II, most of the celebrations were renamed from Decoration Day to Memorial Day. Memorial Day did not become an official holiday until 1967 and its date changed from the traditional May 30 to the last Monday of the month by the Uniform Holidays Act (Public Law 90-363, 5 U.S.C. § 6103(a)) in 1968.

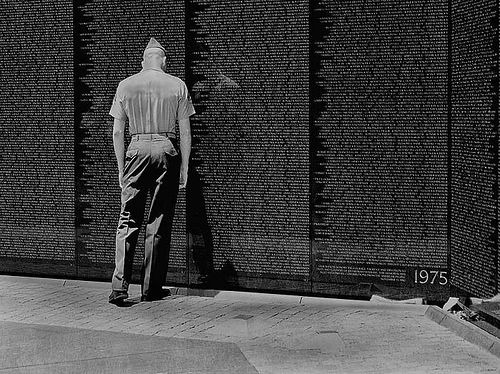

The modern Memorial Day is a holiday celebrating the lives of those sacrificed in defense of the United States and its ideals at home and abroad. Today, we honor the memories of those who paid the ultimate sacrifice so that I can write this blog and you can read it.

Coin images courtesy of the U.S. Mint.

Vietnam Memorial image from Wikimedia.

May 6, 2011 | currency, history

The Maryland Colony was founded by George Calvert, the First Baron of Baltimore, when he sailed from Newfoundland to Virginia in 1629. Calvert travelled up the Chesapeake Bay and settled in the area now known as Saint Mary’s City. Calvert applied to Charles I for a charter in 1630 but died in April 1632 before receiving it. On June 20, 1632, Charles I granted a charter for the colony to Cecil Calvert, the Second Baron of Baltimore. Charles I declared that the colony would be called Maryland, named for the Queen Consort Henrietta Maria.

In 1727, King George II named Charles Calvert the Fifth Baron of Baltimore. Charles then appointed himself Maryland’s governor in 1732, succeeding his brother, Benedict Calvert. When Charles took office, the colonial treasury was in need of funding. Charles used his political connections in London, he was granted permission to authorize and fund the first emission of bills of credit in the Maryland colony.

Calvert arranged for the printing of notes in England to replace low quality tobacco leaves that were circulating as ad hoc currency. The notes were issued in denominations based on the British pound sterling of 20 shillings: 1/- (one shilling), 1/6 (one shilling 6 pence), 2/6, 5/-, 10/-, 15/-, and 20/-. The first issue consisted of £90,000 in bills of credit that were issued as legal tender for most debts except for fees due to a minister or an officer. Each taxpayer was to be given 30/- in notes in return for burning 150 pounds of tobacco currency. History does not record why colonists were paid to burn tobacco. The notes were to be redeemed in 1748 with profits through Calvert’s investments in Bank of England stock that was purchased from the proceeds of a tax on tobacco exports. The notes were engraved in England and the paper was watermarked “Maryland.” When issued, the notes were hand dated with two signers.

Following that first issue, the Maryland Assembly voted to issue smaller emissions for specific purposes. For example, £5,000 was authorized in 1740 to help support a British expedition to the Spanish West Indies. This emission used the stock of unused notes from the 1733 issue but was signed with the current date. In 1749, the Maryland Assembly issued £60,000 in new notes, printed in England using the same plates as the 1733 emission except that the words “New Bill” were added below the denomination.

During the French and Indian War, the British government expected the affected colonies to contribute men and money. Royal Governor Horatio Sharpe asked the legislature to loan £2,000 to the war effort, to be used as rewards for enemy scalps. This emission used the same notes that were backed by a tax on carriage and wagon wheels, import duties on wine and rum, import duties on slaves, and license fees for peddlers. A further emission of £40,000 was authorized to pay for soldiers and the building of defenses to protect Maryland colonists. To support the loan, the Assembly added taxes to bachelors, billiard tables, legal documents, land, and also import taxes on horses, pitch, tar, and turpentine. An emission of £650 was authorized to help the British government pay gifts to allied native nations who fought in the war and a £3,000 loan to Virginia to help their reparations for the war.

In my new quest to find an example of every emission of Maryland Colonial currency, I was able to purchase an unused 1733 1 shilling 6 pence note from Heritage Auctions (pictured above, reverse is blank). The note is graded Choice About New 58PPQ by PCGS Currency. This beautiful note survived the 1733 and 1740 emissions and were saved by souvenir hunters when the Maryland Assembly began authorizing Jonas Green of Annapolis to print notes for later emissions. I am really having fun searching for Maryland Colonial notes.

Jan 28, 2011 | history, national park quarters, US Mint, video

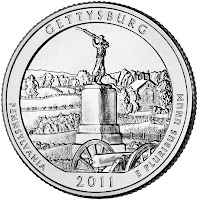

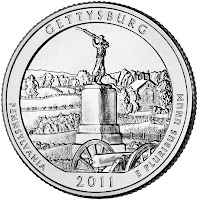

The Battle of Gettyburg was the pivotal battle of the Civil War. The three day battle (July 1-3, 1863) started when Confederate General Robert E. Lee attacked the Union position in an attempt to invade the North after successful battles in Northern Virginia. Gettysburg was defended by Major General George G. Meade who arrived at Gettysburg three days before the battle began. The Confederate Army began its Retreat from Gettysburg on July 4, 1863 following the resounding defeat after (Maj. Gen. George) Pickett’s Charge on Cemetery Hill.

The Battle of Gettysburg is considered the turning point of the American Civil War because of the morale boost it provided the Union forces. But when the battle was over, there was no mistaking the cost of this battle in that between 46,000 and 51,000 Americans died on the battlefield.

The Gettysburg National Cemetery was dedicated on November 19, 1863 with speeches from Edward Everett and President Abraham Lincoln. Everett’s two-hour formal speech at the event preceded Lincoln’s 271-word Gettysburg Address, a speech that proved Lincoln was not a good prognosticator: “The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here….”

The Gettysburg National Military Park came into existence on February 11, 1895 when President Grover Cleveland signed the legislation into law. Originally, the law required the park was to be administered by the War Department. In 1933, control was passed to the National Park Service.

On January 25, 2011, the U.S. Mint launched the The Gettysburg National Military Park Quarter held at park’s Museum and Visitors Center. U.S. Mint Associate Director for Sales and Marketing B. B. Craig and Gettysburg National Military Park Superintendent Bob Kirby co-hosted the event, with Barbara Finfrock, vice chair of the Gettysburg Foundation, serving as master of ceremonies.

The reverse of the quarter depicts the 72nd Pennsylvania Infantry Monument, which is located on the battle line of the Union Army at Cemetery Ridge. It was designed by Artistic Infusion Program Master Designer Joel Iskowitz and engraved by U.S. Mint Sculptor-Engraver Phebe Hemphill.

As with previous releases, the U.S. Mint released an edited B-roll video of the launch with highlights, scenery, production footage.

This is the first quarter in the America the Beautiful Quarters Program representing a piece of United States history. We should always note and long remember what happened in Gettysburg and learn about the events leading up to the worst conflict in U.S. history so that we may never relive that history again.

Jan 23, 2011 | currency, history

I think I may adjust my 2011 collecting goals to finding representative notes of Maryland colonial currency from each emission. While searching an popular online auction website, I found a listing for a note that needed to “come home.” This note did not look like it was in as good condition as my previous purchase, but it looked good enough to represent a new emission.

With money in demand, the Maryland Colonial Assembly authorized an emission of $318,000 in indented bills without legal tender status that would be issued as loans which came due between October 10, 1781 and April 10, 1782. The dollar was tariffed at 4/6 sterling or equivalent in gold or silver. These notes were similar to the release of 1767 except they listed the printers as A.C. and W. Green (Anne Catherine Green and her son William). Jonas Green, Anne’s husband, had died three years earlier. Each bill had two signers, who were Robert Couden, an Annapolis dry goods merchant and mayor of Annapolis from 1786–87, and John Clapham, a landowner in western Maryland who served as sheriff (tax collector) of Anne Arundel County (Annapolis) from 1770–72. These two went into private business together in 1772.

With money in demand, the Maryland Colonial Assembly authorized an emission of $318,000 in indented bills without legal tender status that would be issued as loans which came due between October 10, 1781 and April 10, 1782. The dollar was tariffed at 4/6 sterling or equivalent in gold or silver. These notes were similar to the release of 1767 except they listed the printers as A.C. and W. Green (Anne Catherine Green and her son William). Jonas Green, Anne’s husband, had died three years earlier. Each bill had two signers, who were Robert Couden, an Annapolis dry goods merchant and mayor of Annapolis from 1786–87, and John Clapham, a landowner in western Maryland who served as sheriff (tax collector) of Anne Arundel County (Annapolis) from 1770–72. These two went into private business together in 1772.

This note has a few condition issues that give it the character of surviving 241 years. Aside from the softness of the paper from handling, the center has a fold that is beginning to tear from the bottom and the bottom right corner (obverse) is torn to almost coming off. But the printing is still clear including the signatures of two Maryland patriots.

One of the interesting features of this note is the “J G” included in the right leaf on the reverse of the note for Jonas Green. Green’s influence can also be seen on the obverse of the note on the left border that says “JG Printer · T Sparrow, sculp.” These notes were sculpted by Thomas Sparrow, a Maryland artist who provided most of the border cuts for Maryland colonial currency.

Those who study the history of colonial currency are quick to note that Maryland notes declare that they “shall entitle the Bearer hereof to receive BILLS of Exchange payable in LONDON, or Gold and Silver, at the rate of FOUR SHILLINGS AND SIX PENCE sterline per Dollar for the said BILL.” Notes issued by the Maryland Colonial Council were backed by the profits of Calvert family whose head was Frederick Calvert, the Sixth Lord of Baltimore.

Frederick Calvert was somewhat of a ladies man after becoming the Sixth Lord of Baltimore and Fourth Proprietor of Maryland at the age of 20 in 1751. Aside from having several mistresses, one who published a scandalous autobiography in 1768, he was accused of abducting and raping Sarah Woodcock in London. Although Calvert was acquitted after claiming the encounter was consensual, Calvert escaped to Europe looking to escape his notoriety. Calvert eventually died in Naples in September 1771.

During this time, nobody spoke for the Calvert family and the Maryland assembly continued to freely use the family’s holdings as collateral for these indented bills. Even though Frederick Calvert’s will left the entire Calvert estate to his oldest son, Henry Harford, Harford was only 13 and did not have influence over the assembly’s working even though he was welcomed as the Fifth Proprietor of Maryland. Since Harford was the illegitimate child of Calvert and Hester Whelan of Ireland, Harford was not entitled to ascend to become Lord of Baltimore making Frederick Calvert the last Lord of Baltimore.

Eventually, Harford’s Maryland holdings were seized during the Revolutionary War and used to help fund the government and the Maryland regiments. Harfod returned to Maryland in 1883 and attempted to reclaim the land. Petitions to the Maryland General Assembly failed. His heirs fought for more than 100 years to reclaim the family property. The last case was heard by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1899. In Morris v. U.S., the court denied the family’s claim.

Isn’t it great how one note can open up a segment of history that is not included in your high school history books?!

Click on image to see a larger version.