Oct 31, 2012 | charity, currency, fun, history, pocket change

Before I begin with today’s post, to help the victims of Hurricane Sandy, I urge my readers to donate what they can to the American Red Cross. You can donate online or you can Text REDCROSS to 90999 to donate $10 to the Red Cross Disaster Relief fund. Charges will appear on your wireless bill, or be deducted from your prepaid balance.

Those of us in the D.C. metropolitan area dodged the wrath of Sandy for the most part. There are power outages, trees down, and flooding, but not to the extent north and east of here. It may take a day or two for what passes as normalcy to return to the area but we are in better shape than the coastal areas from the Delmarva Peninsula north to Connecticut and Rhode Island. I wish all of those in the effected areas well and hope their recovery goes as smoothly as possible.

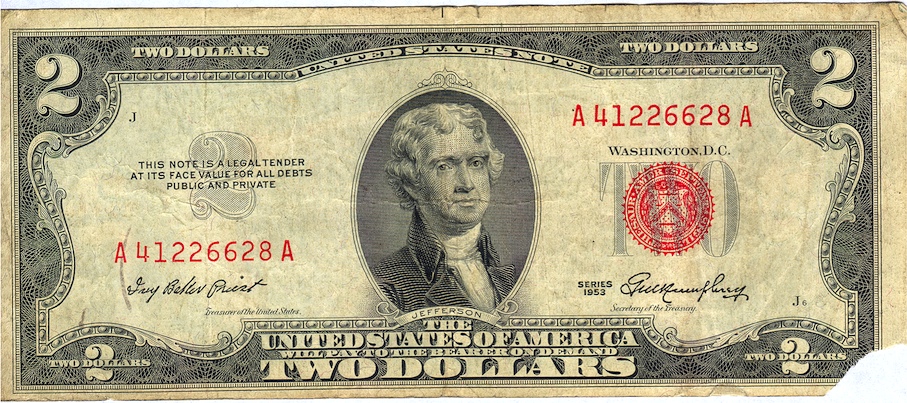

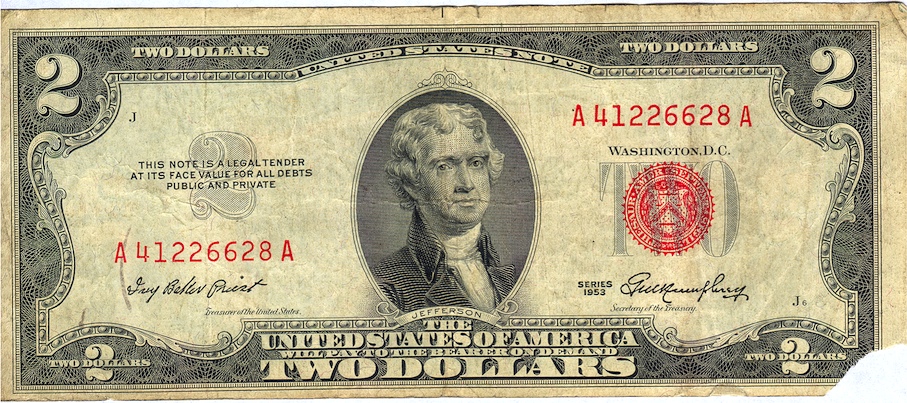

Today’s post is lighter than planned. I rather than do a 2012 version of the numismatic trick or treat as I did last year, I will show off a pocket change find was not found in pocket change and not even change, per se. At our last coin club meeting someone paid for their auction lots with this Series 1953 $2 Federal Reserve Note. Although it is not in good shape and there is a tear in the bottom corner, I decided to take it as part of payment for the lots I sold.

Sec. George M. Humphrey

Thomas Edgar Stephens (1957)–Oil on canvas

Priest Pictured with a hat of money when she announced her candidacy for treasurer of California (circa 1966)

Humphrey was the 55th Secretary of the Treasury serving during Eisenhower’s first term. It was reported that Humphrey gave up a $300,000 annual salary as president of the steel manufacturer M.A. Hanna Company to accept a Cabinet position that paid only $22,500. After retiring from government service, Humphrey returned to Hanna Company and later became chairman of National Steel Corporation.

Long time readers will remember that Priest was the mystery guest on the television game show “What’s my Line” that aired on August 29, 1954. If you forgot, you can go back and watch the video.

Aside from being a political leader in Utah and the 30th Treasurer of the United States, Priest is also the mother of Pat Priest who is better known for playing Marilyn Munster on the 1960’s sitcom “The Munsters.”

Pocket Change Find: Obverse of a Series 1953 $2 Federal Reserve Note signed by Treasurer Ivy Baker Priest and Secretary of the Treasury George M. Humphrey

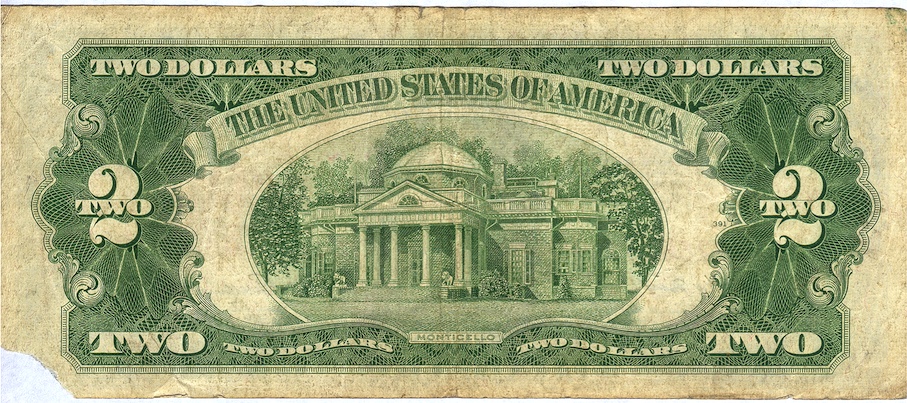

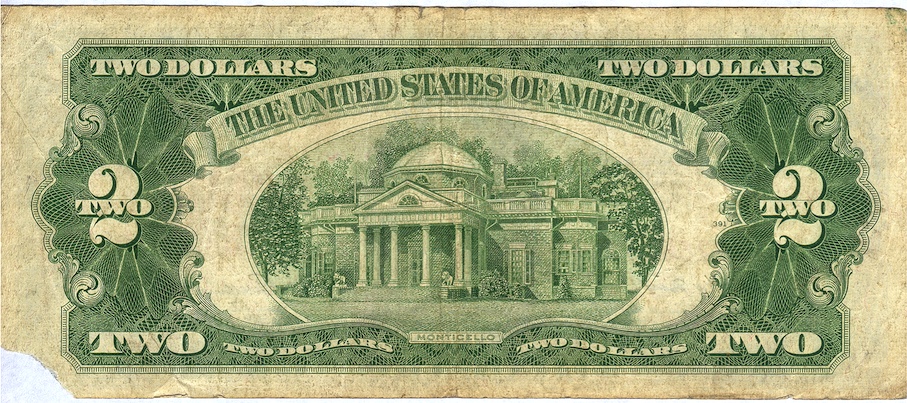

Pocket Change Find: Reverse of a Series 1953 $2 Federal Reserve Note featuring image of Jefferson’s Monticello.

Oct 12, 2012 | bullion, Federal Reserve, gold, history, review

Prior to the very entertaining Vice Presidential Debate, the National Geographic Channel aired a show titled “America’s Money Vault” that was part of their “Behind the Scenes” week. The show was hosted by Jake Ward, editor-in-chief of Popular Science magazine.

The show is centered around the Federal Reserve and primarily the operations of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. After opening the show at Times Square, we are transported downtown to the New York Fed where they are accepting a deposit of over 1 ton of gold. Following an explanation that the New York Fed is the most trusted handler of gold in the world and has 25-percent of the world’s gold on deposit, we watch the transfer process.

As part of the transfer process, the cameras are brought into the vault and the viewers are show “walls” of gold bars. Unlike the images in the 1995 movie Die Hard: With a Vengeance, it appears that the vault that is more solid than the jail-like bars shown in the movie.

Ward visited with Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke to talk about the Fed’s roll in the markets. While in Washington Ward visits the Bureau of Engraving and Printing to show some of the process in currency printing. There was also a discussion with the United States Secret Service about anti-counterfeiting.

One of the more interesting visuals was when Ward visited the East Rutherford Operations Center (EROC), one of the New York Fed’s currency operations. Viewers were shown rows of currency and coins being stored on shelves throughout the building. And in a scene to warm my technical heart, the robotic inventory system was profiled.

According to NatGeo TV, the next time America’s Money Vault will air is on Thursday, October 18, 2012 at 4:00 PM Eastern Time. If you will be away at that time, it is worth setting the DVR (or VCR for those still going old school) to record this show.

Jul 15, 2012 | commemorative, foreign, history, US Mint

For over 80 years since its founding, the U.S. Mint worked to increase production for it to be the sole supplier of coins for the young country. During that time, foreign coins, specifically the Spanish Milled Dollar (8 Real silver coin) was legal tender and served daily commerce. Congress revoked their legal tender status with the passage of the Coinage Act of 1857 making the U.S. Mint the sole supplier of coins in the United States.

Although the U.S. Mint was supposed to be building to supply the country with coins, it was taking on contract minting since it was the only entity with the ability to strike high quality medals. The first record of producing medals for someone other than the government was in 1833 for the American Colonization Society, a group whose purpose was to transport free-born blacks and emancipated slaves back to Africa and settle what today is known as Liberia.

Congress authorized the U.S. Mint to strike circulating coinage for foreign governments with the passage of the Act of January 29, 1874, “Provided, That the manufacture of such coin shall not interfere with the required coinage of the United States.”

The first legal tender coins produced for a foreign government was struck at Philadelphia for the Venezuelan government in 1875-1876 dated 1876-1877. The last circulating foreign coins were struck for Panama in 1983 when congress revoked the authorization because it began to interfere with domestic coin production.

The last time a coin was struck for a foreign country was in 2000 when the Leif Ericson commemorative silver coins were produced for domestic sales and for Iceland. The Iceland coin was struck with a face value of 1,000 Krónur.

Between the first coins struck for Venezuela and the Leif Ericson Commemorative Coin for Iceland, the U.S. Mint produced 1,127 coin types, not including varieties, for 43 countries. Coins were produced in gold, varied fineness of silver, bronze, brass, copper-nickel, nickel, steel, aluminum, and steel. Foreign coins were produced at Philadelphia, Denver, San Francisco, New Orleans, West Point, and Manila.

After the Philippines became a colony of the United States, the U.S. Mint established a branch mint in Manila in 1920. It is the only branch mint outside of the continental United States. Coins struck in Manila used the “M” mintmark making it the first foreign coin produced with a U.S. mintmark. The first foreign coins struck with a mintmark from one of the continental U.S. branch mints was the “P” that appeared on four different foreign coins in 1941. However, these were not the first time a foreign coin was identified as being struck in Philadelphia. In 1895, the word “PHILADELPHIA” was incorporated into the design of the reverse on the Ecuadorian 2 decimos coin.

Jul 13, 2012 | coins, education, history, US Mint

A mintmark is part of the coin design that tells which mint the coins were produced. Using mintmarks to identify where coins were made began in ancient Greece. Coins that were released into circulation were required to have a “Magistrate Mark,” a distinct mark representing the magistrate in charge of producing the coin. If a coin was to have problems, whether by accident or on purpose, the government knows who the responsible party was.

Mintmarks were first used in ancient times as a quality control mechanism. If a coin did not fit the specifications (under or overweight, not the right metal, etc.) it was easy to identify where the coin was made.

Another type of mark made on non-United State coin is a privy mark. A privy mark is a small design added to the coin to identify the where the coin was made, the coiner responsible for the coin, or some other aspect of the coin’s production for quality control purposes. Privy marks fell out of favor in modern times and countries with multiple branches use lettered mintmarks. Some mints use privy marks to differentiate different types of non-circulating legal tender coins.

Mintmarks used on United States coins are as follows:

P: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (1793-present)

The U.S. Mint was formally founded with the passage of the Mint Act of 1792. David Rittenhouse, the first Mint Director, was able to find a building in Philadelphia and begin operations in 1793. The first mint building served the country until 1833. The second mint building served from 1833-1901 and was demolished in 1902. The third mint was in service from 1901-1969. The building is now part of the Community College of Philadelphia. The fourth mint, located two blocks from the location of the first mint building, was opened in 1969 and continues to be used today. Up until 2009, it was the largest mint building in the world. However, no other mint in the world produces more circulating coinage than the Philadelphia mint.

All coins struck in Philadelphia from the founding of the Mint in 1793 until 1980 did not include a mintmark. The exception was the Type 2 Jefferson Nickels minted using the wartime alloy from 1942-1945. Coins struck using the silver-copper-manganese alloy feature a large mintmark above Monticello, including a “P” for Philadelphia.

In 1979, Susan B. Anthony dollars struck in Philadelphia included the “P” mintmark.

Beginning in 1980, all coins struck in Philadelphia, except for the Lincoln Cent, includes the “P” mintmark.

C: Charlotte, North Carolina (1838-1861)

Charlotte became the first branch mint outside of Philadelphia. Authorized in 1835 following the gold strike at the Reed Gold Mine, it first became operational in 1838. The Charlotte branch mint was closed when the building was seized by the Confederacy during the Civil War in 1861. It was not reopened after the war. The Charlotte Mint’s “C” mintmark only appears on gold coins.

D: Dahlonega, Georgia (1838-1861)

The Dahlonega Branch Mint was authorized by congress in 1837 after the Georgia Gold Strike. It opened for production in 1838. Like the Charlotte Mint, the Dahlonega Mint was seized by the Confederacy during the Civil War in 1861 and was never reopened. Gold coins dated 1838-1861 with the “D” mintmark were struck in Dahlonega. Coins with the “D” mintmark starting in 1906 were struck in Denver.

O: New Orleans, Louisiana (1838-1861 and 1879-1909)

The branch mint at New Orleans was authorized by congress in 1836 as part of a discussion to make New Orleans a central trading gateway to the Midwest. This branch mint struck all denominations with the “O” mintmark. In 1861, the building was seized by the Confederacy and used by the Confederate government to strike coins. The Union Army recaptured New Orleans and the building in 1862. Unlike Charlotte and Dahlonega, the New Orleans Mint was eventually reopened. Its second life began as an assay office in 1876. With the passage of the Bland-Allison Silver Act of 1878, the building was refurbished to bring it back to coining standard and was used to strike silver coins, mostly dollars, until 1909. It was closed for the last time in 1909 with production down and Denver taking over the production load.

S: San Francisco, California (1854-1955 and 1968-present)

The San Francisco branch mint was opened in 1854 to assay and coin gold discovered during the California Gold Rush. The first building, known as the “Granite Lady,” was one of the few buildings to survive the Great San Francisco Earthquake of 1906. During the aftermath of the earthquake, Superintendant Frank Leach helped local residents by allowing them to use the grounds as a refuge. A new building was opened in 1937 and celebrated its 75th anniversary in 2012. Today, the Granite Lady is being refurbished as the Museum of San Francisco.

San Francisco produced circulating coins with the “S” mintmark until 1955 when production was suspended and the facility was “downgraded” to an assay office. Production of proof coinage was transferred to San Francisco in 1968 and they began to strike some coinage for circulation until 1974. Since 1975, San Francisco produced only proof coins along with cents without mintmarks to supplement production from Philadelphia. It is not possible to distinguish from no mintmark cents from either mint. San Francisco also produced circulating Susan B. Anthony dollars 1979-1981 with the “S” mintmark. They were granted mint status in 1988.

CC: Carson City, Nevada (1870-1893)

After the major discovery of silver as part of the Comstock Lode in what is Virginia City today, politicians lobbied congress for the formation of a branch mint to assay and strike coins. Congress authorized a mint in 1868 for nearby Carson City and the building was opened for production in 1870. The Carson City branch mint struck silver and gold coins but in lesser amounts than the other mints, making their coins highly collectible and more expensive because of their rarity. The “CC” mintmark is the only two-character mintmark used on U.S. coins.

Production ended in 1893 with the reduced production from nearby silver mines. Starting in 1895 the building served as an Assay Office until the gold recall of 1933. The building was sold to the State of Nevada in 1939 and was turned into the Nevada State Museum.

D: Denver, Colorado (1906-present)

During the Pikes Peak Gold Rush, congress authorized the opening of a Denver assay office in 1863. Congress authorized the building of a branch mint in 1896 and construction began in 1898. Operations from the assay office were transferred to the new building in 1904 and the mint started to strike circulation coins in 1906. Denver struck gold coins until 1933 when gold was recalled. All coins with the “D” mintmark struck since 1906 were minted in Denver. Earlier gold coins dated 1838-1861 were struck in Dahlonega, Georgia.

W: West Point, New York (1976-present)

In 1937, the Treasury built a facility on the northern part of the campus of the U.S. Military Academy to store silver. Originally, it was called the West Point Bullion Repository and was nicknamed as “The Fort Knox of Silver.” From 1968-1973, West Point produced cents without a mintmark in order to supplement the production from Philadelphia. They also produced Bicentennial and Washington Quarters 1975-1979 without mintmarks.

The “W” mintmark first appeared on the 1983 Olympics Commemorative Coins. West Point produces coins for the American Eagle Bullion program without mintmarks but produces collectable versions of the American Eagle with the “W” mintmark. Other commemoratives have been struck at West Point that includes the “W” mintmark.

The same bill that returned the San Francisco branch mint back to mint status in 1983 granted mint status to the West Point branch mint.

M: Manila, Philippines (1920-1941)

After the Philippines became a colony of the United States, the U.S. Mint established a branch mint in Manila. It is the only branch mint outside of the continental United States. The mint opened in 1920 and produced coins in one, five, ten, twenty, and fifty centavo denominations. Coins struck by this mint bear either the “M” mintmark or no mintmark.

Jul 5, 2012 | Baltimore, exonumia, history, museum, shows, silver

Those following the weather-related events around Washington, DC have seen how a little wind can set the local electric companies into a tizzy. Most of us in the effected areas feel that the restoration experience more represents the Keystone Cops rather than a responsible utility company. The last few blog posts have been previously scheduled. Now that power is restored and the refrigerator has been cleaned and restocked, it is time to talk numismatics.

Before the storm, I attended the Whitman Baltimore Expo. While their June show may be the smallest of the three shows that are put on in Baltimore, it still remains a premier show on the east coast, only rivaling its other two shows and F.U.N. for being amongst the best of non-A.N.A. shows. This may be a biased view since the Baltimore Show was the first show I attended when I returned to numismatics following the untimely passing of my first wife. But I am still amazed how Whitman can put on a good show three-times per year!

Friday, after a morning appointment and a delay in leaving, I backed out of my garage and headed to the highway. Over the last year, there is a new highway that will bring me to I-95 a lot quicker than driving down to the Capital Beltway. The ride was a pleasure since it new highway is a toll road and people seem to be allergic to tolls. My problems began when I exited to I-95 North. An accident and two major construction projects extended the usual one-hour trip to nearly two-and-a-half hours! I should be used to this type of traffic living in the D.C.-area, known as the worst on the east coast, but Capital Hill is not the only place where one could find mindless acts.

I could not park in my usual location because it was full, so I was further delayed by trying to find parking near the convention center. Thankfully, my new hip allows me to walk further distances and I was only 35 minutes late for the talk by Don Kagin. While I did arrive in time to take some pictures (a very small sample are on Pinterest), I wish I could have been there for his entire talk.

Before walking the bourse floor, I did have business to conduct, some of which I will discuss at another time. Suffice to say that I took the opportunity to see some people, shake hands, and show my appreciation for their work. Amongst the people I was able to see was Michelle Coiron, Director of sales for Star-Spangled 200 and David Crenshaw, General Manager of Whitman Expos. Both do a great job for their organizations and deserve a sign of appreciation.

Then it was time to hit the bourse floor. As opposed to other times I was at the show, there seemed to be quite a bit activity even as the day wore on. I was pleased to see quite a number of people attended the show that late on a Friday. It keeps the dealers happy and at their tables. I really did not see an exodus begin until about 5:30, about a half-hour before closing.

I spoke with a few dealers who said that business was steady. Most of the coin dealers seemed to be happy while most of the currency dealers called the show a little slow. If anything, I was a little disappointed with some of the currency dealers. With my interest in Maryland colonial currency, I was looking at their inventory for something I could add to my collection. I did not find much colonial currency and what I did was not from Maryland. The only dealer who had any currency in stock from Maryland had 1774 notes, which are the easiest to find.

Since I was late, I passed a number of dealers I spoke with in the past so I could cover as much of the floor as possible. I was not in much a buying mood but I was able to find the 2012 silver one-ounce Chinese Panda and Australian Koala. Both beautiful coins and will be added to what I call my “silver dollar” collection—silver coins 38-40 millimeters in size, like the American Silver Eagle, British Britannia, and Canadian Maple Leaf.

Being in a good mood and wanting to do some thing different, I did spend a lot of time with the exonumia dealers. I saw some really wonderful medals, tokens, and encased coins that really piqued my interest. Rather than buying just anything, which I could have done given my good mood, I applied a little personal discipline and stuck to my goal of finding something neat at every show but limit it to fit in my collection of New York City-related numismatics.

While searching through one dealer’s stock I found my “oh neat” item from New York. What I found was made of pewter, 35½mm in diameter, 3⅓mm thick, and holed on the top. It became irresitable after reading the obverse that says, “Two Cities As One/New York/Brooklyn.” On the reverse in true Victorian style, it says “Souvenir of the Opening of the East River Bridge/May 24th, 1883/1867-1883.” In 1915, New York City renamed it the Brooklyn Bridge.

On May 24, 1883, thousands of people crowded lower Manhattan and Brooklyn for the grandest of all ceremonies from all over the area—even as far away as Philadelphia. The list of dignitaries was a Who’s Who of the political America that included President Chester A. Arthur, New York Governor Grover Cleveland, and New York City Mayor Franklin Edson. The carriage carrying President Arthur and Mayor Edson lead the parade surrounded by a very large cheering crowd.

At 1:50 PM, the processional arrived at the entrance of the new bridge, President Arthur and Mayor Edson left their carriage and crossed what was the world’s longest suspension bridge arm-in-arm to a cheering crowd who paid $2 for tickets to watch from the bridge. The band played Hail to the Chief as ships who came to the ceremony and anchored around the East River blew horns to honor the President. Navy ships who were invited to the ceremonies took turns giving 21-gun salutes.

When they arrive in Brooklyn, they were greeted by Brooklyn Mayor Seth Low The three men locked arms and marched to the Brooklyn Pier (today, the area of Brooklyn Bridge Park) to complete the ceremony dedicating the bridge to the people of the New York City and Brooklyn.

Growing up on Long Island, my late mother insisted that during some of our breaks from school that we play tourist and visit various places in and around New York City to learn about where we are from. During the trips to Rockefeller Center, a place I would work in the 1990s, we would visit the Chase Manhattan Bank Money Museum. Up until it was closed in 1977, it held one of the best collection of numismatic items outside of the Smithsonian Institute. Ironically, the Smithsonian was the recipient of some of the items in the museum following its closure. Another beneficiary was the American Numismatic Society who still retains their part of the Chase Manhattan Collection.

This museum was source of fascination, especially after I learned about collecting while searching through the change I made delivering the afternoon Newsday on Long Island. Somewhere, buried in a box, I have a pamphlet from one of my visits to the Chase Money Museum. I remember the cover was blue and it had a “money tree” on the front. As a youngster, that was significant because my father would lecture me by saying, “money doesn’t grow on trees.” Although the item was made to look like a tree with coins coming off the branches, it was a source of comic relief at home. Otherwise, I do not have a souvenir from the museum. Until now!

Searching through boxes from the same dealer I bought the Brooklyn Bridge medal, I found an encased Lincoln Cent from the Chase Money Museum. In fact, I found several from various dates. Of the ones I found, I bought one with a 1956-D Lincoln Cent that still had its red luster! Even though I could not have visited the museum in 1956—it was before I was born—it was the only coin that looked uncirculated. Rather than try to find one that would have been from the time I could have visited, I picked the better looking coin. Now if I could find my pamphlet, it would make a great part of my New York City collection.

My next show will be the American Numismatic Association’s World’s Fair of Money in August at the Philadelphia Convention Center. I will have a lot planned for those few days and should make for an interesting story. Stay tuned!

Jul 4, 2012 | bicentennial, celebration, commemorative, history

The original Star-Spangled Banner, the flag that inspired Francis Scott Key to write the song that would become our national anthem.

President James Madison, embroiled in a tight campaign for re-election, acquiesced to Congressional “war hawks” from the south and west and declared war on Britain in June 1812. Americans were emboldened by the fact that the British were deeply committed to a war with Napoleon Bonaparte that strained the resources of the crown. There was little acknowledgement in Washington that what passed for a standing army was only about half the size of Britain’s and stationed in widely scattered outposts; that the American Navy totaled about 50 ships to Britain’s more than 850; that coastal defense infrastructure was limited at best; and that there was no core of trained military officers to lead the poorly trained troops and militia. The British ships were much larger than their American counterparts.

Commercial and political interests in New York and New England, concerned about the potential destruction of shipping, opposed the war and in fact, continued to supply the British until the naval blockades were extended. Similarly, Britain saw America as an important market and supplier and only reluctantly responded to the declaration of war.

In the summer of 1812, American troops attempted to invade and conquer Canada. The poorly planned campaign ended in defeat and the withdrawal of the Americans. However, two American frigates, the USS Constitution and the USS United States, gained victories in naval battles, boosting American morale and contributing to President Madison’s re-election.

In response, the British gradually established and tightened a blockade of the American coast south of New York, impairing trade and undermining the American economy.

The attempts to invade Canada during the spring and summer of 1813 were somewhat more successful than the previous year’s, yet they ended in stalemate. By the end of the season, the British blockade had extended north to Long Island.

Remarkably, the young nation prevailed despite a long summer in the Chesapeake region. The British harassed citizens, burned towns and farms, and overwhelmed the scant American naval forces and militia. With the Americans distracted and largely unprepared, the British entered the nation’s capital and burned several public buildings, causing the President, his family and Cabinet to flee Washington. In September, however, an all-out land and sea defense of Baltimore forced the withdrawal of the British from the Chesapeake region. The same month, the British fleet in Lake Champlain was destroyed, leading to the British retreat into Canada. This defeat convinced the British to agree to a peace treaty, known as the Treaty of Ghent, with very few conditions. In January 1815, with neither side aware that the treaty had been signed the previous month, the British decisively lost the Battle of New Orleans. David had defeated Goliath.

The War of 1812 represents what many see as the definitive end of the American Revolution. A new nation, widely regarded as an upstart, successfully defended itself against the largest, most powerful navy in the world during the maritime assault on Baltimore and later at the Battle of New Orleans. America’s victory over Great Britain confirmed the legitimacy of the Revolution; established clear boundaries between eastern Canada and the United States; set conditions for control of the Oregon Territory; and freed international trade from the constraints that had led to the war. America emerged from the war with an enhanced standing among the countries of the world.

The war served as a crucial test for the U.S. Constitution and the newly established democratic government. In a bitterly divided nation, geographically influenced partisan politics led to the decision to declare war on Great Britain. Unprepared for war, under-financed, threatened by secession and open acts of treason, the multi-party democracy narrowly survived the challenge of foreign invasion.

Star-Spangled Banner Commemorative Coins

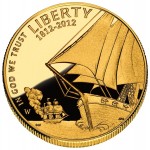

The 2012 Star-Spangled Banner Commemorative Coins are being sold by the U.S. Mint with the proceeds from the sales ($35 for each gold coin and $10 for each silver coin) to support the Maryland War of 1812 Bicentennial Commission.

-

-

2012 Star-Spangled Banner Gold Commemorative Obverse depicts a naval battle scene from the War of 1812, with an American sailing ship in the foreground and a damaged and fleeing British ship in the background. Designed by Donna Weaver and engraved by Joseph Menna.

-

-

2012 Star-Spangled Banner Gold Commemorative Reverse Depicts the first words of the Star-Spangled Banner anthem, O say can you see, in Francis Scott Key’s handwriting against a backdrop of 15 stars and 15 stripes, representing the Star-Spangled Banner flag. Designed by Richard Masters and engraved by Joseph Menna.

-

-

2012 Star-Spangled Banner Silver Commemorative Obverse depicts Lady Liberty waving the 15-star, 15-stripe Star-Spangled Banner flag with Fort McHenry in the background. Designed by Joel Iskowitz and engraved by Phebe Hemphill.

-

-

2012 Star-Spangled Banner Silver Commemorative Reverse depicts a waving modern American flag. Designed by William C. Burgard III and engraved by Don Everhart.

The commission will use these funds to support its bicentennial activities, educational outreach, and preservation and improvement of the sites and structures related to the War of 1812. Help support the commission’s activities by purchasing a commemorative coin today!

Jun 23, 2012 | Baltimore, commemorative, history

Following the end of the American Revolutionary War in 1783, Britain concentrated its efforts in colonizing Canada and defending itself in Europe. After the turn of the century, the British Empire was threatened by France with the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte.

As the new nation was forming and expanding, the British were also expanding and began to recruit Native American Tribes to agitate the Americans. The British were also hijacking American merchant vessels, many trading with France.

Some historians call War of 1812 the United State’s second revolutionary war. The primary reason for declaring war on Great Britain was after years of the Royal Navy harassing or capturing merchant ships bound for France. At the time, England was in the middle of the Napoleonic Wars and was trying to prevent France from getting the supplies it needed. This lead to President James Madison writing a letter to congress explaining England’s actions. Although Madison did not call for a declaration of war, the Democrat-Republican lead congress voted to declare war on Great Britain (79-49 in the House, 19-13 in the Senate). Madison signed the declaration on June 18, 1812. It was the first Declaration of War passed by the new nation.

To commemorate the bicentennial of the start of the what has been called America’s Second Revolutionary War, the Star Spangled 200 and the Maryland War of 1812 Bicentennial Commission held Sailabration in Baltimore’s Inner Harbor.

The week long celebration featured concerts, vendors, tours of Fort McHenry, tall ships, air show by the famous Blue Angels, and more.

As part of the celebration, the Star Spangled 200 organization was present to sell the 2012 Star-Spangled Banner Commemorative Proof Silver Dollar and promote the sale of the other options.

To assist the Star Spangled 200 organization and the coin clubs of Maryland, the organization invited the Maryland State Numismatic Association to set up a table on the side of their tent to promote the coin clubs of Maryland. MSNA and the Montgomery County Coin Club Vice President, your blog host, staffed the table on Sunday.

Aside from promoting collecting and the clubs of Maryland, I was also able to help talk with visitors about the 2012 commemorative coin to the various visitors. For seven hours, I stayed with the wonderful staff of the Star Spangled 200 organization talking with many visitors.

May 16, 2012 | gold, history, rareties, shows

I continue to be amazed with the stories some coins garner. Last week, I received a note announcing that one of the only two known 1907 rolled edge Indian Head $10 Eagle Proof gold coins will be exhibited at the up coming Long Beach Coin, Stamp & Collectibles Expo.

The coin is own by Monaco Rare Coins of Newport Beach, California and has been graded by Numismatic Guarantee Corporation as Satin PR67.

“This important and monumental rarity was not discovered to be a proof finish until several years ago. It was previously misattributed as mint state. The coin now is insured for $3 million,” said Adam Crum, Vice President of Monaco Rare Coins.

According to Crum, there are some researchers who believe that this coins may have been owned by President Theodore Roosevelt. As part of Roosevelt’s “pet crime,” he worked with prominent sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens to redesign U.S. coinage. Prior to his death, Saint-Gaudens completed the design of the Indian Head $10 gold Eagle and the iconic $20 gold Double Eagle, both introduced in 1907.

“One prominent numismatist told me, ‘After all the research we did, your coin has to be Teddy’s,’” Crum said. “Obviously, more research is required, but that is what being a numismatist is all about, isn’t it? I look forward to more discovery.”

Even if the coin was not owned by Teddy Roosevelt it is still a great story!

If you are in the Long Beach area, the show runs Thursday and Friday, May 31 and June 1, from 10 a.m. to 7 p.m.., and Saturday, June 2, from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Drop by and see this historic coin!

Apr 14, 2012 | cents, history, policy

Since the Canadian government has proposed the elimination of their one-cent coin from production and putting in measures to remove them from circulation, proponents of a similar policy in the United States have been pointing northward and the past to support their position. When they point to the past, the target is the Half-Cent, established as part of the Coinage Act of 1792 and eliminated by the Coinage Act of 1857.

The common argument is that if the United States could eliminate an unpopular low-denomination coin in the 19th century, why can’t we do this in the 21st century?

In order to understand why that question is a non-sequitor, you have to look back at the history of the half-cent.

After the passage of the Constitution by the constitutional convention, Alexander Hamilton wrote extensively for both the Federalist Papers and spoke in many venues how the a strong, centrally managed currency would improve commerce between the new states and promote the nation as a whole in foreign trade. While this view was shared by others, how to implement a new currency system became controversial.

On January 28, 1791, Hamilton submitted the Secretary of the Treasury Report, “On the Establishment of a Mint” to the House of Representatives. Hamilton tied the value of the basic unit to the Spanish Milled Dollar (8 reales) and called the basic unit a “dollar.” In that report, Hamilton proposed a simple system of currency that included a ten and one dollar gold coins, one and one-tenth dollar silver coins, and one-hundredth and two-hundredth copper coins. Hamilton surmised that using smaller denominations would standardize production around a few coins that could be produced in sufficient numbers to supply commerce.

While mostly in agreement with Hamilton’s report, Thomas Jefferson had another idea. Jefferson thought it would be better to tie subsidiary coins tied to the actual usage of the 8 reales coin. At the time, rather than worry about subsidiary coinage, people would cut the coin into pieces. A milled dollar cut in half was a half-dollar. That half-dollar cut in half was a quarter-dollar and the quarter-dollar cut in half was called a bit.

The bit was the basic unit of commerce since prices were based on the bit. Of course this was not a perfect solution. It was difficult to cut the quarter-dollars in half with great consistency which created problems when the bit was too small, called a short bit. Sometimes, short bits were supplemented with English pennies that were allowed to circulate in the colonies.

As an aside, this is where the nickname “two bits” for a quarter came from.

Jefferson felt that in order to convert the people from bit economy to a decimal economy, the half-cent was necessary to have 12½ cents be used instead of a bit without causing problems during conversion from allowing foreign currency to circulate as legal tender until the new Mint can produce enough coinage for commerce.

Much against Hamilton’s wishes, congress agreed and made the half-cent along with the eagle, half-eagle, quarter eagle, silver (not gold) dollar, half-dollar, quarter-dollar, disme (later renamed dime), cent, and half-cent. After the bill was passed and signed by President George Washington on April 2, 1792, Washington decided to put the new Bureau of the Mint under the jurisdiction of Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson to ensure that the currency system would be implemented since Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton objected to these provisions of the law.

As the new Mint ramped up production, there were other issues with U.S. coinage that overshadowed any perceived controversy that the half-cent would have received. Over the next 60 years, laws were passed to change the composition of coins, ratio of gold-to-silver, and even the problem with melting that caused the suspension of producing the silver dollar in 1804.

The half-cent would come into focus in the 1850s when the cost to produce the United State’s copper coins was nearly double their face value. In 1856, the Mint produced the first of the small cents, the Flying Eagle small cent, and produced 700 samples to convince congress to change to the small cent. As part of the discussion was the elimination of foreign currency from circulation making the U.S. Mint the sole supplier of coins.

There is no record of outcry from the public on the elimination of the half-cent. Its elimination came four years after the Coinage Act of 1853 that created the one-dollar and double eagle gold coins in response to the discovery of gold in North Carolina, Georgia, and California. The gold rush caused a prosperity and inflation that not only made the half-cent irrelevant but not something on the public’s mint. In that light, the Mint and congress felt that it just outlived its usefulness and would not be necessary with the elimination of foreign currency from circulation.

More controversy was generated in 1857 over the demonetizing foreign coins in the United States than the elimination of the half-cent. While the half-cent continued to circulate, it was estimated that one-third of the coins being circulated were foreign, primarily reales from Mexico. Redemption programs did not go smoothly, but in the end foreign coins were taken out of the market and the American people adapted and it could be said we prospered.

Comparing the elimination of the half-cent in 1857 with the trying to eliminate the one-cent coin today is like saying one baseball player is better than another because he hits a lot of home runs. Just like there is more to consider than hitting home runs in baseball, there is more to the discussion than pointing to an event that happened 155 years ago without considering entire picture.

Apr 13, 2012 | BEP, education, history, US Mint, video

Originally released on March 30, 2012 and updated on April 12, the Department of the Treasury updated their video honoring the history of women working for the U.S. Mint and the Bureau of Engraving and Printing over its history. The video also honors the 220th Anniversary of the U.S. Mint and the 150th Anniversary of the BEP.

Introduced by Treasurer of the United States Rosie Rios, the video shows how both the U.S. Mint and the BEP have a history of providing opportunities for women since each agencies founding.

Considering that women were considered second class citizens in the 18th century, it is amazing to find out that within two years the U.S. Mint hired two women to be adjusters. When the BEP was founded in 1862, women were hired alongside men and held the majority of positions within four years. I do not think any other agency in the U.S. government has a similar recrod.

,

,