Weekly World Numismatic News for March 8, 2020

Much of the news this week was by media outlets announcing local coin shows.

Much of the news this week was by media outlets announcing local coin shows.

While the big shows are delightful, local coin shows can be more fun. Smaller shows do not attract the type of crowd that you will see in a larger venue, like a convention center. Fewer people go to these local shows making it a more relaxed atmosphere.

Behind the tables at these shows are local dealers, some who may not be able to afford to set up at national shows. These are your neighbors. They are the ones you can go to for information and help you find that hard to find or intriguing coin.

The relaxed atmosphere of the small show makes it an excellent time to talk with everyone about collecting.

I will try to visit the Whitman Baltimore Expo in two weeks and the World’s Fair of Money in August. Between now and then, you might find me a few local shows in Maryland and Northern Virginia. Go check out a local show. You’ll be glad you did!

And now the news…

→ Read more at streetwisereports.com

→ Read more at streetwisereports.com

→ Read more at ancient-origins.net

→ Read more at ancient-origins.net

→ Read more at mydailytribune.com

→ Read more at mydailytribune.com

234 Years and Counting

After nearly a year of war and attempted negotiation with King George III and the British parliament, it became clear that the colonies in the New World would continue to be under harsh rule without representation. In January 1776, the Continental Congress met to discuss the matter.

After nearly a year of war and attempted negotiation with King George III and the British parliament, it became clear that the colonies in the New World would continue to be under harsh rule without representation. In January 1776, the Continental Congress met to discuss the matter.

Public support for independence from the British Empire was growing amongst the colonies. Only the “middle colonies” of New York, New Jersey, Delaware, and Maryland who were benefiting financially being part of the British Empire were against independence. When these colonies sent delegations to the Continental Congress, each of their conventions did not allow them to vote for independence.

As the war with Great Britain dragged on and the attempt at tightening their reigns on the colonies persisted, the populous cry for independence grew. Delegates were set back to their governments and representatives sent to the middle colonies to convince them that the colonies had to declare independence for their own survival. As colonies began to line up with the independence movement, Pennsylvania, New York, Maryland, and South Carolina remained reticent on the subject.

Of the four hold outs, Pennsylvania and Maryland had governments with strong ties to the colonial governors who still had influence. John Adams wrote a draft preamble to explain the independence resolution. Part of the way the resolution was written was, in effect, to overthrow the colonial governments of Pennsylvania and Maryland so that it would be replaced by a popular government. On May 15, 1776, that preamble was passed. The colonies had taken their first step toward independence.

Of the four hold outs, Pennsylvania and Maryland had governments with strong ties to the colonial governors who still had influence. John Adams wrote a draft preamble to explain the independence resolution. Part of the way the resolution was written was, in effect, to overthrow the colonial governments of Pennsylvania and Maryland so that it would be replaced by a popular government. On May 15, 1776, that preamble was passed. The colonies had taken their first step toward independence.

Delegates left the congress and returned to their own colonial conventions. Maryland, whose delegates walked out of the congress in protest, continued to reject the notion of independence. Samuel Chase returned to Maryland and convinced them to allow their delegates to approve the motion of independence. Pennsylvania, New York, and South Carolina remained against the declaration while the Delaware delegates were split.

On June 11, 1776, the “Committee of Five” was appointed to draft a declaration. Committee members were John Adams of Massachusetts, Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania, Thomas Jefferson of Virginia, Robert R. Livingston of New York, and Roger Sherman of Connecticut. Although no minutes were kept from the committee meetings, it was accepted that the resulting document was largely Jefferson’s work. The Committee of Five completed the draft on June 28, 1776.

On June 11, 1776, the “Committee of Five” was appointed to draft a declaration. Committee members were John Adams of Massachusetts, Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania, Thomas Jefferson of Virginia, Robert R. Livingston of New York, and Roger Sherman of Connecticut. Although no minutes were kept from the committee meetings, it was accepted that the resulting document was largely Jefferson’s work. The Committee of Five completed the draft on June 28, 1776.

Debate on the draft began on July 1. After a long day of speeches a vote was taken. Maryland voted yes but Pennsylvania and South Carolina voted no. The New York delegation abstained with out authority from their government to vote. Delaware could not vote because its delegate was split on the question. Edward Rutledge of South Carolina moved to postpone the vote until the next day.

Although there is no written history on what happened that evening, there had to have been lobbying by supporters of independence because on July 2, South Carolina voted yes followed by a turnaround by the Pennsylvania delegation that also voted yes. New York with no authority from their government continued to abstain. With the Delaware delegation deadlocked, this set up the historical ride of Caesar Rodney. Rodney was one of Delaware’s representative to the Continental Congress. He was in Dover attending to other business when he learned that Thomas McKean and George Read were deadlocked on the vote of independence. Rodney rode 80 miles from Dover to Philadelphia to vote with McKean to allow Delaware join eleven other colonies voting in favor of independence.

Although there is no written history on what happened that evening, there had to have been lobbying by supporters of independence because on July 2, South Carolina voted yes followed by a turnaround by the Pennsylvania delegation that also voted yes. New York with no authority from their government continued to abstain. With the Delaware delegation deadlocked, this set up the historical ride of Caesar Rodney. Rodney was one of Delaware’s representative to the Continental Congress. He was in Dover attending to other business when he learned that Thomas McKean and George Read were deadlocked on the vote of independence. Rodney rode 80 miles from Dover to Philadelphia to vote with McKean to allow Delaware join eleven other colonies voting in favor of independence.

With 12 votes for independence and one abstention, the Continental Congress approved the declaration. Jefferson then set forth to make the agreed upon corrections to the document. On July 4, 1776, the Continental Congress approved the wording of the Declaration of Independence. The document was sent to the printer for publication and distribution to the public.

Although historians debate exactly when the final document was signed, it is accepted that the final signatures were added on August 2, 1776. Since New York approved the resolution of independence on July 10, the New York delegation is included amongst the signatures.

As we celebrate the 234th Birthday of the United States of America, please take a moment to remember those who fought for our freedom and continue to do so today. Honoring them is the best way to honor those whose vision created this great nation.

Picture Credits

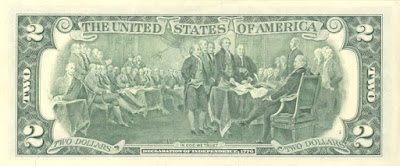

Kennedy Bicentennial Half and $2 Federal Reserve Note reverse are from Wikipedia

Other coin images are courtesy of the U.S. Mint

BREAKING NEWS: CCAC Forms Subcommittee On Coin Design

According to the tweets of Citizens Coinage Advisory Committee member Donald Scarinci (@Scarinci), CCAC Chair Gary Marks announced the establishment of a subcommittee to help U.S. Mint Director Ed Moy to initiate his vision for a neo-renaissance of U.S. coins. Members of the subcommittee will be made up Mitch Sanders, Donald Scarinci, Roger Burdette, Heidi Wastweet, and Gary Marks. Their report due by October 31, 2010.

During a presentation at the FIDEM conference on September 19, 2007, held in Colorado Springs, Moy said, “I want and intend to spark a Neo-Renaissance of coin design and achieve a new level of design excellence that will be sustained long after my term expires.”

Recently, Moy and the U.S. Mint came under attack from both the CCAC and the Committee of Fine Arts for the “overall disappointment with the poor quality” of the alternatives presented for the 2011 commemoratives,” as written in a letter to Moy from the CFA sent on May 28, 2010.

During the 2010 FIDEM conference, there were reports that the design of U.S. coins were not up to the standard set by Moy during his 2007 talk. None of the attendees to the conference in Finland would comment for the record, but the off the record comments were less then complementary about U.S. coin and medal designs.

Scarinci reported that “Support for the creation and mission of the historic first subcommittee of the CCAC is unanimous.” The CCAC included the May 28 letter from the CFA as part of their record.

When Theodore Roosevelt became president in 1901, he initiated the “Golden Age of American Coin Design.” Using his bully pulpit, he held the designs of the U.S. Mint’s Chief Engraver Charles E. Barber in contempt and ordered coinage whose designs were more than 25 years old to be redesigned. Roosevelt was a fan of sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens and asked Saint-Gaudens to redesign the small cent. Rather than use the Liberty design in an Indian Headdress for the small cent, it was used on the 1907 $10 gold coin. Roosevelt also asked Saint-Gaudens to design the $20 gold double eagle coin to rival the beauty of all classic coins.

Roosevelt called this his “pet crime.”

With the decent of the political bureaucracy it would be impossible for a modern president to follow the example of Roosevelt. For those of us who lament the poor quality of the designs emanating from the U.S. Mint, we should support this new subcommittee and hope the figure out how to “fix” the processes and artistry of coin designs.

CCAC Meets This Week in Colorado

Members of the Citizens Coinage Advisory Committee are in Colorado this week for their monthly meeting to be held on June 28, 2010 at Colorado College. The meeting corresponds with the first week of the American Numismatic Association’s Summer Seminar.

CCAC members met in Denver this morning for a closed-door administrative meeting at the U.S. Mint’s Denver facility. According to the tweets from CCAC member Don Scarinci (@scarinci), the meeting included U.S. Mint Chief Engraver John Mercanti, the Mint’s chief marketing director, and the chief counsel.

After the meeting, Scarinci tweeted, “Based on morning conversations, tonight’s CCAC meeting will be quite lively. It is time for CCAC to demand change.” It will be interesting to watch his tweets during the meeting.

A Brief Look at the History of Anti-Counterfeiting

When the British first founded colonies in North America, currency was limited to coins whose value was based on their metal content. When the King taxed his colonies to pay for wars in Europe, the colonies looked for ways of financing their own governments to provide services.

Since it was illegal for the colonies to coin money, they issued paper notes. These notes functioned as currency but actually were bills of credit, short-term public loans to the government. For the first time, the money had no intrinsic value but was valued at the rate issued by the government of the colony in payment of debt. Every time the colonial government needed money to pay creditors, they authorized the printing of a specified quantity and denomination of notes. Laws authorizing the issuance of notes were called emissions. The emission laws also included a tax that was used to repay the bills of credit with interest.

As taxes were paid using the paper currency, the paper was retired. As the notes were removed from circulation, that meant less payments the government had to make. On the maturity date, people brought their notes to authorized agents who paid off the loan. Agents then turned the notes over to the colonial government for reimbursement plus a com- mission. Sometimes, colonies could not pay back the loan. They instead passed another emission law to cover the debt owed from the previous emission plus further operating expenses, buying back mature notes with new notes. The colonists accepted this system since it was easier than barter and there were never enough coins to meet commercial needs.

Counterfeiting was rampant by the mid-18th century. In order to combat the problem, Benjamin Franklin devised the nature print, an imprint of a leaf or other natural item with its unpredictable patterns, fine lines, and complex details made it more difficult to copy.

To create a nature print, Franklin placed a leaf on a damp cloth. The cloth was placed on top of a bed of soft plaster that pressed the leaf into the plaster. Once the plaster hardened, it had a negative impression of the leaf. Molten copper was then poured over the plaster to make the printing plate. Franklin first used nature prints for the 1737 New Jersey emission. He also used different leaves for different denominations and elaborately engraved borders to further thwart the efforts of potential counterfeiters.

Franklin partnered with David Hall printing notes for New Jersey and Pennsylvania colonies. Along with his nature print, Franklin also included the phrase “Tis Death to Counterfeit.” Aside from trying to scare away potential counterfeiters, the penalty for counterfeiting in the 18th century was death. No convictions for counterfeiting colonial currency or death sentences have been recorded.

Later, Hall partnered with William Sellers to print Pennsylvania currency when Franklin was sent to England by the Pennsylvania assembly as their colonial agent.

Other printers tried different methods to thwart counterfeiters. James Parker of Woodbridge, New Jersey printed notes in two colors. With printing a labor intensive process, it was thought the process to cumbersome for counterfeiters to go through the process of the second printing. Also, Parker used red ink as the second color. Red was more expensive than black ink in the 18th century.

In Maryland, William Green of Annapolis used other anti-counterfeiting measures included using random wavy (indented) borders that had to match the original stub book, elaborate engravings, random punctuation, and superfluous characters. The example to the right is a “Half of a Dollar” from the Maryland emission of March 1, 1770. On this example, the engraver’s initials “TS” (Thomas Sparrow) appear at to the top, a small “a” was inserted between “half” and “dollar” while there is an accent mark over the “a” in “Exchange.”

In Maryland, William Green of Annapolis used other anti-counterfeiting measures included using random wavy (indented) borders that had to match the original stub book, elaborate engravings, random punctuation, and superfluous characters. The example to the right is a “Half of a Dollar” from the Maryland emission of March 1, 1770. On this example, the engraver’s initials “TS” (Thomas Sparrow) appear at to the top, a small “a” was inserted between “half” and “dollar” while there is an accent mark over the “a” in “Exchange.”

Anti-counterfeiting technology has become very advanced since the colonial days. When the Bureau of Engraving and Printing introduced the new $100 Federal Reserve Note, its anti-counterfeiting technology included a watermark, a security thread, color-shifting ink, micro-printing and a new security ribbon that appears to animate as the note is tilted.

Anti-counterfeiting technology has become very advanced since the colonial days. When the Bureau of Engraving and Printing introduced the new $100 Federal Reserve Note, its anti-counterfeiting technology included a watermark, a security thread, color-shifting ink, micro-printing and a new security ribbon that appears to animate as the note is tilted.

Rather than threatening death on today’s notes, our currency is protected under laws enforced by the U.S. Secret Service. The U.S. Secret Service was formed in 1865 as part of the Department of the Treasury following the Civil War to stop counterfeit currency that was printed in an to attempt to wreck the union economy. It was estimated that up to one-half of the currency in circulation was counterfeit.

The responsibility to protect the president, vice president, their families, and other national officials was added to their responsibilities in 1901 following the assassination of President William McKinley.

Today, the U.S. Secret Service is part of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security with the same mission to protect U.S. money from counterfeiting. They reported that during fiscal year 2009, there were 2,506 domestic arrests for counterfeiting as well as assisting with 360 foreign arrests. This helped remove $182 million in counterfeit currency from circulation proving they are one of the world’s premiere law enforcement organization.

Maryland Currency image courtesy of the Coins and Currency Collection at the University of Notre Dame.

Image of the new $100 FRN complements of the United States Bureau of Engraving and Printing.

More on the ANA In Chicago

American Numismatic Association Executive Director Larry Shepherd was interviewed by David Lisot for CoinTelevision.com about the ANA’s decision to base its summer World’s Fair of Money in Chicago.

Shepherd opens his remarks saying that “[this] is not a knee jerk reaction as some publications made it out to be.” He reiterated that this was a well thought process. The problem seems that each one of his arguments have answers that could be addressed with another perspective. Here are counters to two of his main points.

One of the factors Shepherd cites as a reason for Chicago being a good place for a coin show is the lack of other major coin shows in the area. It is interesting that the ANA did not consider the Chicago International Coin Fair (CICF) and Chicago Paper Money Expo (CPMX) major shows. CICF and CPMX have been held in the Rosemont area for a while and is now owned by Krause Publications, founded by Board of Governors member Chet Krause and where President Cliff Mishler was once CEO. In addition to CICF and CPMX, the Mid America Coin Expo was moved the Schaumburg in 2008 and starting next year, the Central States Numismatic Society moved their annual show to Rosemont for 2011 and Schaumburg for the succeeding five years.

Even if you discount the CSNS show because of timing, that is three major shows already in Chicago. Although Shepherd can argue that the World’s Fair of Money is a bigger show, it is probably the biggest coin show in North America, if not the world. So why not share the wealth with other cities?

The other issue that Shepherd brought up is that he said that (paraphrasing) an organization cannot call up a city and say you are bringing the world’s largest coin show to their city in a few years—tell the mayor. After consulting with someone in another industry confirmed what Shepherd said that cities are looking for a financial commitment. They want the organization to guarantee floor space (and associated rent) in the convention center and hotel usage that will represent the potential income from the various taxes governments charge.

Shepherd mentions that meeting the guarantees is becoming difficult because of online travel sites that undercut the prices agreed upon in the contract to use the city facilities. If the organization does not sell the minimum guaranteed rooms, the organization must make up the tax losses to the city. What Shepherd does not tell you is that an organization can negotiate this with the city. What he does say is that this is that this is not an issue in Chicago… except that the location is not in Chicago. The proposed location is in Rosemont, just east of Chicago O’Hare International Airport and 17 miles northwest of downtown Chicago. It is also a limited access area with a limited number of hotels nearby making guarantees unnecessary since most people going to the show will stay in a nearby hotel.

Rather than trying to negotiate with municipalities to host a show that does millions of dollars of business in addition to a multi-million dollar rare coin auction, Shepherd recommended this enclave outside of Chicago near the second busiest airport in the United States surrounded by suburbs and not exactly a tourist destination.

In the past, Shepherd discussed the scheduling and handling of the ANA shows so as to not lose money. One consideration was to find what he described as “a good bourse city” primarily to make the dealers happy. What he never mentioned is what would make the ANA collectors happy. Rather, Shepherd is saying that it is not enough to use what is probably the world’s largest numismatic show as the destination in different cities as outreach to its members and future members, the ANA, a non-profit organization, is using the show to make a profit and enforce profits for its dealers. I am for dealers making profits, but I am against this profit motive as a driving factor for the placement of the ANA convention.

The Chicagoland area is a wonderful place and Chicago is a great city. But to be the only area that the ANA uses for its premier convention is an insult to cities all over the country capable of hosting a successful show and an indictment on Shepherd’s inability to think creatively.