May 18, 2018 | advice, coins, shows, values

If you are a collector of anything you know that the price of your collectible is based on both a market valuation and what you are willing to pay. There are a lot of market valuation tools for the numismatic collector. One of the more popular ones is The Coin Dealer Newsletter and associated publications that track market trends.

In 2012, I wrote a two-part series about how coins are priced (see Part I and Part II) where I discussed not only how the coins are priced by the different markets for purchasing coins. Last year I wrote about other venues to buy your coins and then earlier this year I added information about estate auctions. All have their audiences, which expands the buying options.

One important factor I discussed is how to negotiate. In “How Are Coins Priced (Part II),” I wrote about negotiating from the perspective of the collector. At the time, I had just started my collectibles business and did not have the experience from the other side of the negotiation table to understand from their perspective.

I thought about this when I stumbled upon an article in Sports Collectors Digest about negotiating. The author spoke to collectors and dealers about their negotiating styles and conditions for negotiating. While the information about negotiating from the collector’s perspective is not that different than what I originally wrote, the impression from the dealer’s perspective is what I have witnessed.

My experience and the article provides two aspects of negotiating from the dealer’s perspective that I want to highlight here.

First, I want to emphasize the concept of BE POLITE! While most people are polite, there have been times I have wanted to punch a customer in the mouth. While I do not mind a little aggressive negotiating being rude will not make me want to work with you on the price.

Second, understand that you are not only buying an item but selling each collectible comes with a cost. Aside from the cost of the inventory, the dealer has overhead. At a show, the dealer has travel expenses. In a shop, there are expenses with maintaining the store.

Even auctions have expenses. Seller fees can be from 25 to 50-percent of the sale price in many professional auctions. Even eBay charges a final value fee for selling on their site and sometimes there are listing fees. While you might complain about paying more than the postage for the shipping costs, there are labor and material costs for packaging your winning item in addition to the postage.

To highlight the issue, the author spoke with a baseball card dealer who said:

This dealer also wanted another “fact of doing business” relayed to others here. He wasn’t saying the mark-up on his items always came to 100 percent of his original purchase price for those items. Rather, if he buys a card for, say, $50, he has to sell that same card for roughly $100 because within that price would be his other costs (lodging, food, transportation, and so forth). Therefore, when the other expenses are factored in, in reality he may be making just 10 percent profit on that card.

The same thing could be said for numismatics as well.

Apr 24, 2018 | coins, fun, values, video

Passing the time after 10:00 PM on Monday night, the television found its way to the History Channel for the return of Pawn Stars, the reality show about a pawn shop in Las Vegas. While the first show of the hour was just interesting it was the second show that started at 10:33 PM that was more intriguing.

Although the show was marked as “NEW” on the visual guide, it first aired last January. To make sure I was able to study the coins more, I found the episode on the History Channel website. It is also available on YouTube at https://youtu.be/yTKbcAKbQtU. (embedded below)

Opening the show, a seller name Walter walked in with two rare coins. The first coin was a 1792 Half Disme and the other a silver Libertas Americana. Two coins dating back to the earliest days of the country’s history.

If you recognize Walter his full name is Walter Husak. In 2008, Husak sold his extraordinary collection of large cents at an auction held during that year’s Long Beach Expo. For this show, he was selling the two coins.

The 1792 Half Disme was graded MS-65 by Numismatic Guarantee Corporation who lists the coin as a TOP POP, meaning no coin has graded higher. There are only two half dismes graded MS-65 by NGC and one appeared on Pawn Stars.

-

-

1792 Half Disme obverse graded NGC MS-65 TOP POP (screen grab)

-

-

1792 Half Disme reverse graded NGC MS-65

(screen grab)

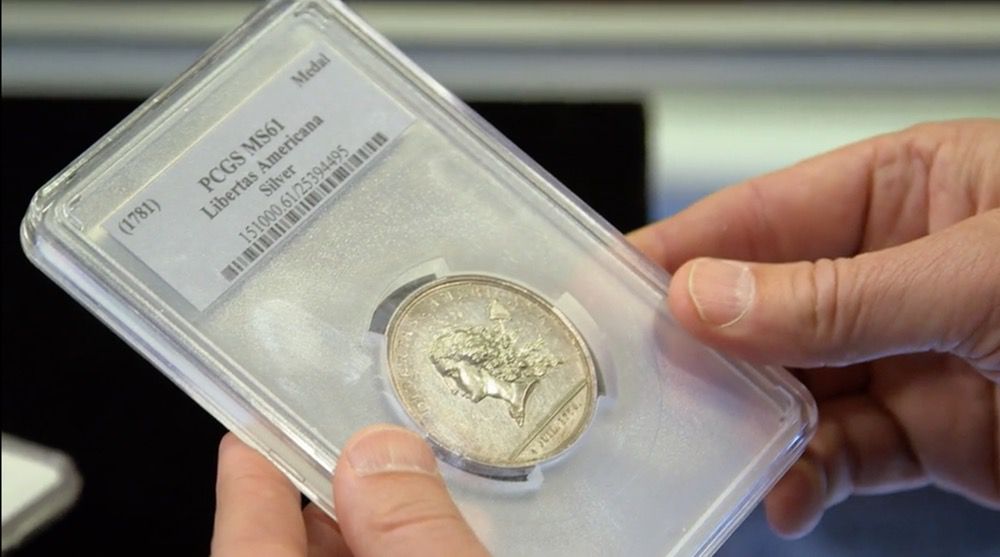

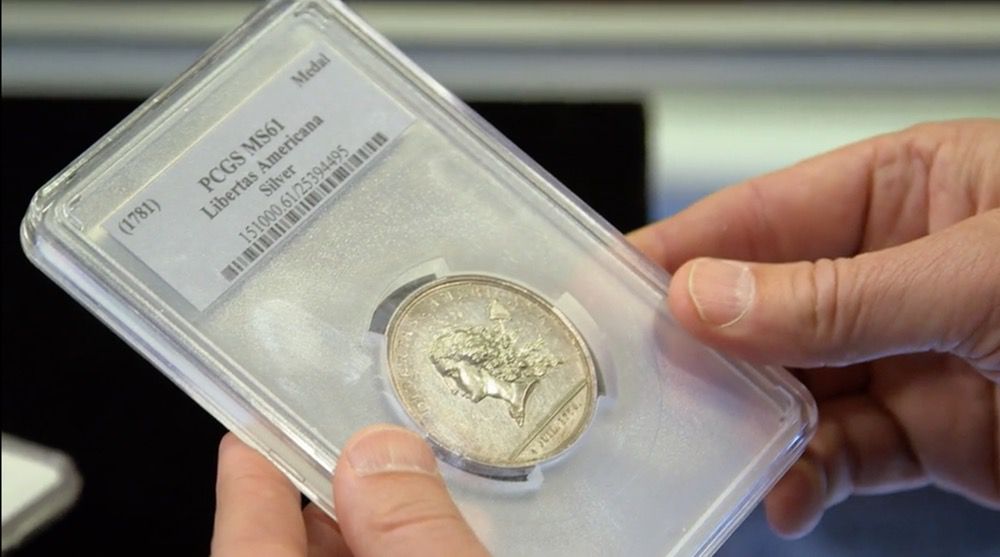

The Libertas Americana is one of the rare silver versions and was graded MS-61 by Professional Coin Grading Service

-

-

obverse of the silver Libertas Americana graded MS-61 by PCGS (screen grab)

-

-

Reverse of the silver Libertas Americana

(screen grab)

As with a lot of these purchases, Rick calls in an expert for assistance. This time, the expert is Jeff Garrett, the founder of Mid-American Rare Coin Galleries in Lexington, Kentucky and immediate past president of the American Numismatic Association.

Jeff Garrett stands next to Walter Husak as they examine the Half Disme and Libertas Americana on Pawn Stars (screen grab)

I noted that Garrett’s firm is in Lexington since the location of the television show is in Las Vegas. While doing a little online investigation into the prices and to see if there was more information, there was a note on the Collectors Universe forums suggesting that the segment was not a reality, but it had been staged.

According to user “cardinal,” he wrote:

Jeff Garrett is one of the experts that gets brought in to evaluate numismatic items for the show. For this specific episode, Jeff was looking for both a half disme and a Libertas medal, and Jeff was able to locate them and had the respective owners’ permission to have them appear on the show. The half disme is pedigreed to the Garrett Collection, and the silver Libertas medal was one that Jeff Garrett had sold some years back. (This particular Libertas medal has been in the Cardinal Collection for the past 6 years.)

I believe Ccardinal is the anonymous person behind the Cardinal Collection who has collected some of the finest coins in the PCGS registry.

Following a discussion on the actual Libertas Americana used for the show, he ends with:

During the show, the half disme was a no-sale. The Libertas medal was shown as sold at $150K on camera. That being said, the piece was not actually sold, even though Rick actually did want to buy it for $150K.

I have heard stories as to how some segments are real and some are staged. When I spoke with Charmy Harker about her appearance in 2012, I was under the impression that her attempt at selling a World War II-era aerial bomber camera was not overly staged. That does not seem to be the case in this episode.

My one complaint is that these two esteemed numismatists mispronounced the name of the coin. Everyone kept pronouncing disme as “DIZ-ME.” In reality, disme is pronounced as if the “s” was not included in the word. Disme is derived from the French term for tenth but pronounced dime—which is why the “s” was dropped after the first issues of 1792 coins.

Oh well… it was a fun segment to watch.

Apr 10, 2018 | coins, commentary, education, US Mint, values

I write this blog from the perspective of a collector. I champion the collector. I think that collectors are the most qualified to determine the direction of the hobby. The collector is the consumer and the consumer is almost always right.

When it comes to helping with the direction of the hobby dealers should also have a say. Their input is important. But they should be there to support the collector because without collectors the dealers have no business. Dealers should not be dictating the direction of the hobby.

Are these sets hurting the hobby? Should the U.S. Mint stop producing them? (U.S. Mint image)

Regular listeners to The Coin Show knows that Matt is not a fan of modern coins and the products of the U.S. Mint. In fact, during the last show, he admitted to not carrying American Eagle coins because he does not want to support the U.S. Mint in damaging the hobby.

During the podcast, Mike came to the defense of U.S. Mint collectors but that defense was tempered when he said that collecting U.S. Mint products was for beginner collectors and that it was a way to start before the collector “graduate” to other collectibles.

I have questioned Matt and Mike in the past on Facebook but this time I felt their statements crossed a line. My regular readers know I can get hyperbolic but I try to remain respectful. As it happens on Facebook and anywhere else on the Internet, people cannot take the words at face value and have to read something into them.

This time I emphasized that not only do I collect U.S. Mint items but have not “graduated” to the type of collectibles Mike and Matt proclaim to be real collectibles. New readers can go through this blog and see how my collection can be classified as normal to eclectic.

After a lot of angry discussions (you will see a sample below) and some churlish responses from others (not Matt or Mike), I finally coaxed out the reasons for Matt’s hatred of modern U.S. Mint products. Unfortunately, it seems his reasons have more to do with the industry than the U.S. Mint.

According to Matt, the U.S. Mint is harming numismatics by selling annual sets like proof and mint sets at the prices they set. During the Facebook discussion, Matt and Sam Shafer, another Indianapolis-area dealer, said that they believe the U.S. Mint’s prices are too high.

From their perspective as dealers, they claim it is the U.S. Mint’s fault for the differences between the manufacturer’s suggested retail price the secondary market.

Using that logic, can I blame Chevrolet for the secondary market price of the 2014 Silverado I just purchased? If I tried, General Motors would laugh me under the tonneau cover of the truck! Yet, coin dealers are applauded for applying the same logic. This does not make sense.

How can you blame the manufacturer for the secondary market’s reaction?

Matt wrote, “I feel like the depreciation seen in modern sets is much more harmful to potential collectors or beginning collectors.”

I guess if General Motors followed that logic, they would stop making trucks!

But we are talking about collectibles. In that case, Topps, Fleer, and Upper Deck should stop producing baseball cards.

This is only an argument by dealers who would rather sell what they like and not take a broader view of the collecting market. In my new life, I am a collectibles and antiques dealer. The items I buy are either from the secondary market or I buy new items from manufacturers such as comic book and baseball card publishers.

This 1901 $10 Dollar Lewis and Clark Bison note (Fr# 122) was sold by a dealer at an antiques show by a dealer not complaining about the collecting market.

The vast majority of dealers are very good and very reasonable. Many do understand the view of the collector and work with them. However, there is a subset of dealers that can be some of the most stubborn business people I know. They refuse to change with the market. Even if the market is not looking for their niche, they will not adapt to the market. Their mind is made up do not confuse them with facts.

They are also the most vocal in their opposition to market forces. Their usual retort is “you don’t understand, you’re not a dealer!”

With all due respect, I do not need to be a dealer to know that not changing with the times is doing more to hurt the hobby than the U.S. Mint is by doing its job.

Did you know that the Pobjoy Mint struck this coin under the authority of the British Virgin Islands. Is this good for the hobby? (Pobjoy Mint image)

The U.S. Mint does not offer dozens of non-circulating legal tender (NCLT) coins. U.S. Mint coins are struck and not painted. The U.S. Mint does not offer piedfort version of circulating coins or even coins guilt in gold or palladium. The U.S. Mint does not make deals with movie production companies, comic book publishers, or soft drink manufacturers to issue branded coins.

Every coin that the U.S. Mint offers for sale has an authorizing law limiting what they could produce. According to those laws, the U.S. Mint has to recover costs and is allowed to make a “reasonable” profit.

But what is reasonable? This is a question that has a lot of valid arguments on both sides. However, the U.S. Mint is subject to oversight by the Treasury Office of the Inspector General (OIG) and, occasionally, review by Congress’s Government Accountability Office (GAO). Neither oversight agency has produced a report saying that the U.S. Mint’s prices are unreasonable.

The U.S. Mint is selling what they manufacture at a price that the competent oversight agencies have not complained about. The only one complaining is by the dealers in the secondary market.

Why are these dealers complaining?

We get to the crux of the problem when Sam Shafer responds, “I would rather sell a customer a Morgan dollar than a set of glorified shiny pocket change.”

It does not take a rocket scientist to understand why a dealer would write that. A dealer makes more money selling Morgan dollars than modern coins. It is about business, not about what the U.S. Mint is doing. It is also a very reasonable response if the dealer would own up to the fact that it is about the impact to their business. Blaming the U.S. Mint is like crashing into a wall and blaming the wall for being there!

But Sam must have had some bad experiences: “How about you come down from your pedestal, put your loudspeaker up your rectum and work in a shop for a few years where you can witness the devastation of families first hand for a few years.”

This is a strong statement, even if you discount the placement of inanimate objects into bodily orifices they do not belong. What has the U.S. Mint done to cause “devastation?” The U.S. Mint sells products to those who want to buy them. You are not forced to buy from the U.S. Mint.

Sam continues, “While your [sic] at it maybe you can take up your glorious cause of finding homes for the 50 billon [sic] sets the government produced and bulk sold over the years to the collectors who assumed that 5 sets would better than 1.”

By Sam’s logic, it is the U.S. Mint’s fault that someone speculated and the investment did not pan out? Whose fault is that? Who told someone that buying these sets would be a good investment? Not the U.S. Mint! Where does the U.S. Mint say in any of its publications or website that coins make a solid investment? How could these speculators have come to this conclusion?

2018 Fiji Coca-Cola Bottle Cap-shaped coin is not a U.S. Mint product. It contains 6 grams of silver (about $3.20) and costs $29.95. Is this good for the hobby? (Modern Coin Mart image)

The U.S. Mint does not even acknowledge historical and aftermarket pricing for the items they manufacture.

The U.S. Mint sells collectible coins. They do not sell investments.

Over the years, I have received more complaints about dealers than allegedly worthless State Quarters or the U.S. Mint’s annual sets. But why are coins allegedly worthless?

Did the U.S Mint make claims that these one-time-only coins are really special and that they would be the greatest thing since sliced bread?

This is not a U.S. Mint Product! (Danbury Mint image)

Did the U.S Mint create books, boards, folders, albums, maps, touting this as a once-in-a-lifetime way to collect?

All this came from the secondary market. Who runs the secondary market? DEALERS!

DEALERS set the values for the coins based on what they sell them for.

DEALERS take coins and entomb them in sonically sealed plastic holders saying that this is how you should be collecting. They tell you one encapsulating service is better than another and then make you pay different prices if you use a service they do not like even if the number assigned as a grade is the same on both pieces of plastic.

DEALERS have convinced an entire class of collectors that if they do not have a plastic holder with this new, whiz-bang label that their collection is not complete.

Tragedy grips the industry when a Pawn Star is featured on a plastic holder’s label! (NGC image)

DEALERS genuflect when someone puts a shiny green sticker on a plastic holder as if it was blessed by some deity. They prostrate themselves if the plastic holder is granted that divine gold sticker! After preaching this gospel to their flock, you are considered a heretic if you question the validity of the sticker and the motives of the sticker maker.

While the U.S. Mint is not perfect, the problems with the numismatic market have not been created by a tightly regulated government bureau. The problems come from the secondary market whether they are overstating the values of these items or demeaning collectibles that they cannot make a hefty profit on.

Maybe it is time for dealers to look in the mirror and ask whether the U.S. Mint is hurting the hobby or maybe they are refusing to recognize the problem is right in front of them.

Oct 9, 2016 | medals, silver, US Mint, values, video

Finding coins in pocket change can be a lot of fun. Then there are those who find hoards of coins buried in the ground or just stored somewhere that people forgot. From shipwrecks to treasure hunts, we all dream of finding the next jackpot somewhere.

Finding coins in pocket change can be a lot of fun. Then there are those who find hoards of coins buried in the ground or just stored somewhere that people forgot. From shipwrecks to treasure hunts, we all dream of finding the next jackpot somewhere.

On your great grandfather’s farm, a worker was plowing the field and found a silver medal. It has the image of President James Madison on one side and what looks like a peace medal on the other. Rather than letting go, great grandpa traded three hogs for the medal.

The medal gets handed down from generation to generation until one of his ancestors takes the medal to Antiques Roadshow to find out what it is worth.

You are told that it is a silver James Madison Indian Peace Medal. The 1809 medal was designed by assistant engraver John Reich and struck at the U.S. Mint in Philadelphia. It is not the largest of the medals but at 2½-inches, it is a fairly significant medal.

What is it worth? See what Jason Preston of Jason Preston Art Advisory & Appraisals of Los Angeles said about the medal on Antiques Roadshow:

Did you guess right?

Image and video courtesy of

WGBH and the Antiques Roadshow

Oct 22, 2015 | coins, markets, news, values

Earlier this year, Shane Downing, editor and publisher of the Coin Dealer Newsletter, better known and “The Greysheet” died of colon cancer on Jun 18, 2015. Shane became publisher following the death of his father, Ron Downing, in 1997.

Earlier this year, Shane Downing, editor and publisher of the Coin Dealer Newsletter, better known and “The Greysheet” died of colon cancer on Jun 18, 2015. Shane became publisher following the death of his father, Ron Downing, in 1997.

The Downings have been running The Greysheet since 1884 when Ron and Shane’s grandmother Pauline Miladin purchase the publication from its original owners.

The Downings expanded the publication to include quarterly supplements, The Currency Dealer Newsletter (Greensheet) for currency, Certified Coin Dealer Newsletter (Bluesheet) for certified coins, and special monthly supplements highlighting specific coins. In recent years, CDN has been available online as a PDF file in a program they call CDNi.

Early last month it was announced that an ownership group led by John Fiegenbaum, formerly president of David Lawrence Rare Coins (DLRC), has purchased CDN Publishing. The ownership group includes Steve Halprin and Steve Ivy, co-founders of Heritage Auctions; Mark Salzberg, Chairman of Numismatic Guaranty Corporation; Steve Eichenbaum, CEO of the Certified Collectibles Group, the parent company of NGC. Fiegenbaum has retired from DLRC to dedicate his time to running CDN with the assurance that CDN will remain an independent entity. The other owners will remain in their current positions.

John Feigenbaum receives 2014 Abe Kosoff Founder’s Award from the Professional Numismatic Guild

CDN will be moving from California to the east coast. Although the press release does not specify the location, it is likely that CDN will be located in Virginia Beach, Virginia where Fiegenbaum has been running DLRC for over 30 years.

One of the benefits of Fiegenbaum running CDN would be to improve online access to their publications. Under Fiegenbaum, DLRC has moved from mail and phone bid auctions to a successful online auction system. Their auction website is very user friendly and getting better as they receive feedback from users. DLRC’s website rivals that of Heritage Auctions, led by Halprin and Ivy, for ease of use and accessibility to the auction items. This is a powerful backing for better electronic access.

Using the resources of NGC and Heritage Auctions, CDN could produce an online almanac of coinage including history and prices that would rival anything currently available. Making it accessible to collectors and dealers on both a free and paid basis could keep CDN viable for many years to come. Such a service could even surpass the every-ten-year effort by CoinWorld and the multi-volume effort by Whitman Publishing.

While running DLRC, Feigenbaum has shown how embracing the Internet could benefit his company and the collecting community. If he can embrace electronic publishing by bringing existing resources to the Internet and look for expansion with specialty collectors, CDN could become the go-to resource for people interested in learning all about their collections by making it more accessible to the emerging market of Gen X’ers and Millennials. That would benefit the numismatic community more than phonebook sized volumes of dead trees or glossy pages with pretty red covers.

Image of The Greysheet cover courtesy of CDN Publications.

Image of John Feigenbaum courtesy of David Lawrence Rare Coins.

Sep 12, 2014 | bullion, coins, gold, halves, US Mint, values

If you have not seen what has been going on in the gold market, the prices have been falling. The financial press has not provided a single reason as to why the gold market is going down but there is a consistent view that the United States economy showing strength with unemployment dropping and low inflation may be alleviating fears in the markets. Stocks are rising and it is suspected that investors are selling their gold shares in order to participate in the bull market.

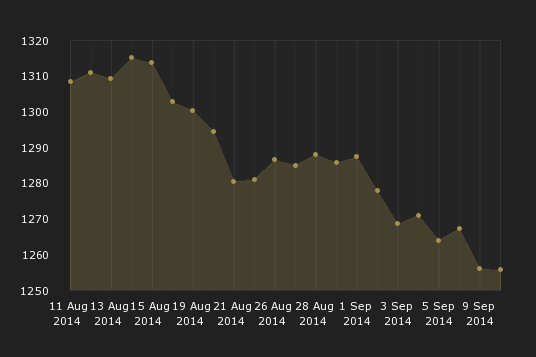

For collectors it means that the U.S. Mint could adjust the prices of precious metal products. In particular, the price is coming down that could affect the price of the Kennedy gold half-dollar. Based on the table published in the Federal Register [PDF], if the London Fix price of gold falls below $1,250 per troy ounce, the price of the coin will drop to $1,202.50 or $37.50 below the $1,240 issue price.

The London Fix is now managed by The London Bullion Market Association. Gold prices are set by an auction that takes place twice daily by the London Gold Fixing Company at 10:30 AM and 3:00 PM London time. Auctions are conducted in U.S. dollars. The benchmark used by the U.S. Mint is the PM Fix price on Wednesday.

On September 10, 2014, the London PM Fix was $1,251.00 which will leave the price of the Kennedy gold half-dollar $1,240.

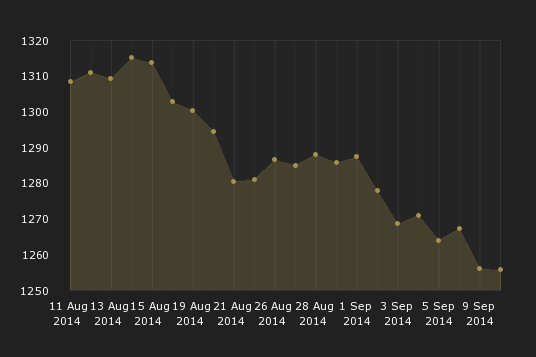

London PM Gold Fix for the month leading up to September 10, 2014

London PM Fix on September 10 was $1,251.00

Prices are in U.S. dollars

A strong economy is good for many reasons. In this case, when the price of gold drops the price of gold coins also drops. While this is not good for investors, it benefits collectors who will buy one or two coins for their collections. It also means that the value of the inventory that the dealers who spent a lot of money and effort in order to be first will be worth less than previously. After all, if the U.S. Mint is going to produce as many coins as the demand, then the public is better off saving money and buy from the U.S. Mint.

As anyone who has invested money will tell you that it is dangerous to try to time the market. I am sure that if you can figure out when the price of gold will be at its lowest while the U.S. Mint is still selling the Kennedy gold half-dollar, I know a bunch of people on Wall Street who want to talk with you. That being said, I have a feeling that the trends are in favor of waiting to see what happens. Although I have not decided whether I will buy a coin, I am going to wait to see what the market does. If the price of gold continues to fall, I could be convinced to buy one of these coins for myself.

Pricing for the 2014 50th Anniversary Kennedy Half-Dollar Gold Proof Coin

As published in the Federal Register (

79 FR 38127)

on July 3, 2014

| London PM Fix |

Item |

Sale Price |

| $1000.00 to $1049.99 |

¾ Troy oz |

$1,052.50 |

| $1050.00 to $1099.99 |

¾ Troy oz |

$1,090.00 |

| $1100.00 to $1149.99 |

¾ Troy oz |

$1,127.50 |

| $1150.00 to $1199.99 |

¾ Troy oz |

$1,165.00 |

| $1200.00 to $1249.99 |

¾ Troy oz |

$1,202.50 |

| $1250.00 to $1299.99 |

¾ Troy oz |

$1,240.00 |

| $1300.00 to $1349.99 |

¾ Troy oz |

$1,277.50 |

| $1350.00 to $1399.99 |

¾ Troy oz |

$1,315.00 |

| $1400.00 to $1449.99 |

¾ Troy oz |

$1,352.50 |

| $1450.00 to $1499.99 |

¾ Troy oz |

$1,390.00 |

| $1500.00 to $1549.99 |

¾ Troy oz |

$1,427.50 |

| $1550.00 to $1599.99 |

¾ Troy oz |

$1,465.00 |

| $1600.00 to $1649.99 |

¾ Troy oz |

$1,502.50 |

| $1650.00 to $1699.99 |

¾ Troy oz |

$1,540.00 |

Fixing chart courtesy of London Gold Fixing Company.

Mar 12, 2013 | books, coins, Red Book, review, values

Merriam-Webster’s online dictionary defines almanac as “a usually annual publication containing statistical, tabular, and general information.” Almanacs have been around for a while in various forms from the earliest times of writing to today. Early almanacs were simply calendars of coming events and records of past events. They included holidays, phases of the moon, and significant dates that related to the weather for the farming community.

Although there have been many almanacs that bridged into the modern era, none had been as famous as Poor Richard’s Almanack written by Benjamin Franklin writing under the pseudonym Richard Saunders. Franklin published Poor Richard’s Alamanck from 1733-1758. Amongst the surviving almanacs include The Old Farmer’s Almanac that has been published continuously since 1792, the Farmer’s Almanac that has been published continuously since 1818, and The World Almanac and Book of Facts published since 1868. These are the almanacs that all others are judged against.

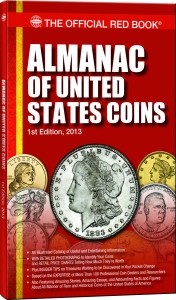

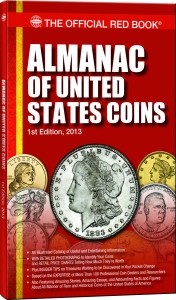

Having grown up with The World Almanac, reading the Central Intelligence Agency’s The World Fact Book, and being a begrudging fan of the Coin World Almanac, I was interested when Whitman Publishing sent out a notice that they just released the First Edition of the Almanac of United States Coins.

Having grown up with The World Almanac, reading the Central Intelligence Agency’s The World Fact Book, and being a begrudging fan of the Coin World Almanac, I was interested when Whitman Publishing sent out a notice that they just released the First Edition of the Almanac of United States Coins.

Although I read the description, I did not read it carefully because when I opened the package sent to me by Whitman, I found a skinny trade paperback-sized book. I reread the Whitman press release and it said the book was 192 pages. Initially, I felt disappointed in my hopes that there would be a competitor on the market to the Coin World Almanac since competition makes everyone better. So I can get over my initial reaction, I put the book down for a while to overcome my initial reaction to give the book a fair review.

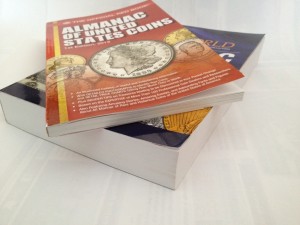

After two weeks, I find I cannot hide my disappointment especially when I place the book next to the Coin World Almanac. Now in its eighth edition, the Coin World Almanac is 688 pages of numismatic reference that is a worthy comparison to any almanac in any industry. The problem with the Coin World Almanac is that it is updated every ten years. Having purchased the last two, the seventh edition seemed stale by 2004. I suspect the eighth edition will begin to feel stale by the end of this year if not by mid-2014. Maybe Coin World should consider shortening their update cycle.

Coin World does not have to worry about competition from Whitman. For as much as Whitman has invested in creating content across their “Official Red Book Series” from the many great authors, their Almanac of United States Coins is so lacking in content that it is many years away from being able to compete.

The only complement I can offer Whitman for this book is that many of the coin images are superb. I do like the images showing the relative grading of the individual series but wish it was expanded to include a few more grades. One example that would help collectors is that the difference between a VF-20 and MS-65 Walking Liberty half dollar is so vast, that having at least two intermediate grades (e.g., EF-40 and AU-50) would be helpful.

Whitman’s Almanac v. Coin World’s Almanac: In this case, size matters!

Whitman is going to have to learn that every numismatic reference book does not have to be a price guide. If they want to include type set-like guides, then do not make it look like a major component of the book. Otherwise, I would recommend people read A Guide Book of United States Type Coins instead. Thus the first improvement I would make is either eliminate the price guide information or find a way to minimize it as a central focus of each section. After all, an almanac is supposed to be about the content and the fact. Price guides are opinions that change with market forces that changes from the end of the editorial cycle until the book is published.

I know Whitman wants to sell books and has to find a way to make this book unique over their other offerings so they do not cannibalize sales, but they have to consider that they may never sell some of these books to certain people anyway. And if Whitman drops the pricing information, that still leaves their other books as an option for the reader. After all, Whitman can include a line at the end of each coin’s section that if they want in-depth information, the read can “consult” Whitman’s other book on the coin.

It is interesting how Whitman included a list of the authors for all of their books as credits but did not print the name of the editor of this book. However, Whitman’s press release named publisher Dennis Tucker as the editor.

Now that Whitman has disappointed me, they need to look at the content they have already invested in with their current books. They can start by taking whatever information is in the Red Book (A Guide Book of United States Coins), the Red Book Professional Edition, and the Blue Book (Handbook of United States Coins) and bring the content together to improve the current almanac. Just doing this would greatly improve this book. Then, it is a matter of an editor either convincing Whitman’s other authors to build on the chapters or distill the information in their other books to something suitable for an almanac.

I really wanted to like this book to the point that I put it aside in order to see if I could get over my first impression. Instead, I started to read another Whitman book that deserves the good review I will write in the near future. But I could not get over the disappointment. The text has no depth, facts that should be in an almanac are missing, and it seems like a glorified coin type price guide. Maybe they should market this as something for the very beginner, even for someone under the age of 12. Therefore I give this book a grade of F-12. The only factor that prevents this book from grading lower are the images. It is not a book I can recommend.

DISCLOSURE: Whitman Publishing provided the copy of the book I reviewed. I will not add this book to the library. It will be donated to my coin club’s annual charity auction in December with the proceeds going to the local Boys and Girls Club.

Cover image courtesy of Whitman Publishing.

Aug 7, 2012 | books, coins, iPad, review, values

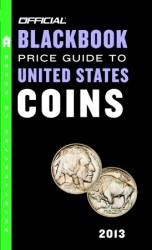

Regular readers know that I am an advocate of the electronic world, especially when it comes to references that should be available in a more portable manner than paper. While dead tree editions will continue to be produced, certain references deserve to be provided in electronic form for portability.

Regular readers know that I am an advocate of the electronic world, especially when it comes to references that should be available in a more portable manner than paper. While dead tree editions will continue to be produced, certain references deserve to be provided in electronic form for portability.

In the collecting world, price guides are great to have in electronic form. You can carry them on your smart phones or tablets when you go to shows to have some idea what your potential purchase is worth. Understand that printed price guides are not the best source for prices. Prices can change daily, even hourly depending on market conditions including the costs of metals. At least the price guides will provide a general idea of the item’s value.

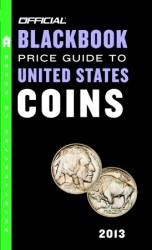

Price guides have more value than the prices. Some have very good and even excellent numismatic information. We know about the usual suspects in this area, but a reference to look at is The Official 2013 Blackbook Price Guide to United States Coins. The Official Blackbook is now in its 51st Edition.

I was provided an electronic review copy by the publisher with the only condition that I write this review.

Starting with the format, I cannot argue with that it is available as an e-book and complies with the full EPUB standard where the contents work, is searchable, allows bookmarks, and works well even on the iPad’s pedantic e-reader. Because e-book readers do not handle tables well, they have to be embedded as images (EPUB 3, which is still in development, should change this). However, The Official Blackbook does it in a way that makes it easy to resize them on smaller devices like the iPhone.

E-book usability issues should not be taken lightly. It is easier for publishers to publish e-books as PDF files or using other tricks that does not take advantage of the electronic formats. House of Collectibles, an imprint of Random House Reference, should be commended for doing this right.

One nice feature added by the publisher is the “Fast-Find Coin Reference Index.” This is a list of coin types, like Colonial Coins, and the name of the coin (e.g., Brasher Doubloons) that are clickable links back to the text. My only complaint is that this is the last entry in the Table of Contents and could be missed by the reader. Even though it is toward the end, I would move the entry near the top because it is that useful.

As a price guide, it is as good as any on the market with multiple price points, showing the differences between types, and mintages for each year. The tables do carry over the check box from the print edition that could be used to mark coins owned, but that is of limited usefulness in the electronic version.

After the price guides are very useful chapters about the contents of U.S. coinage. The chapters, “Primary Metals,” the silver and gold coin value charts, and the weights and measures are very good references. While other books have them interspersed within their pages, I like having this information in their own chapters.

Each section starts with a 2-3 page description on each coin type noting history, major varieties, and some design information. Where there are interesting subtleties between types, the authors provide images for the reader as a reference. Some references do this inline with the price guide, I like the idea of showing the images first and leaving the price tables as clean as possible.

At some point, the authors need to consider updating some of the numismatic writing and think about how to make it a better reference than just a series of articles. For example, the chapter “Coin Auction Sales” needs to be updated to include how most auction houses now offer Internet bidding, some are exclusively Internet bidding, and that the section’s author, Q. David Bowers, has not worked at Bowers and Merena in quite some time—I believe it was 2003 when he sold is interest in the company which since 2010 has become part of Stack’s Bowers.

The chapter “Expert Tips on Buying and Selling Coins” has some good information but needs to be updated to include buying over the Internet, using online auctions, and to separate the section on grading. In fact, the section about grading could be greatly enhanced as a standalone chapter and provide a better service to readers.

One chapter that either has to be rewritten or deleted from future books is the “Mobile Computing…” chapter. Aside from being seriously out of date with today’s online and mobile world, it is heavily slanted to support the business model of section author’s company. While it would not be bad for the author to include a blurb about their company at the end of the chapter, the entire chapter reads like one of those worthless white papers that I receive from computer vendors on a daily basis.

The two chapters that make the book worth buying is are the chapters “Erros and Varieties” and “Civil War Tokens.” Both chapters are very well written, informative, and if you do not learn something from either chapter, then you are not reading carefully. Although the author is not listed with the chapter, Mike Ellis s listed as a contributor. For those who are unfamiliar with Ellis, he is currently the CONECA Vice President and a leading expert in variety and errors. Having heard him speak in the past, having this chapter written by him is a great addition to the book and worth reading.

I also thought the chapter “Civil War Tokens” by Dale H. Cade was phenomenal. I never really thought about Civil War Tokens and their impact on commerce because of the coin shortages, but it was a fascinating read. In fact, I am re-reading this chapter because I know I missed some things while reading it for this review. I know I will now look at Civil War tokens in a different light.

There are other areas like Civil War tokens that the authors/editors of the book should consider adding as well as other impacts on U.S. coinage.

The bottom line is that after 51 years, it may be time to find a new editor to update this book and make it more reflect modern references. It has some great information, some good information, some information that is just plain useless, and there is information that could be added to enhance the book. But the great really shines while the good needs a little updating to make it great. For these reasons, I give the book a grade of MS62 with hopes that the 52nd edition will be better. I think that a proper refresh could make The Official Blackbook rival its red-colored counterpart.

Jan 23, 2012 | coins, education, values

Understanding how coins or any numismatic item is priced cannot be complete without the final transaction between the current owner of a coin to a new owner. The current owner could be a dealer, auction house, or another collector that is looking to sell a coin. Each seller has different motivations for selling and different factors goes into the final price that you might pay when buying that coin.

Wholesale versus Retail

In Part I, I mentioned that there was a difference between the “price” of the coin and it’s “value.” The price of the coin is what you pay when you buy the coin—sometimes called the retail price. The value of the coin is what a dealer will pay you for the coin—also called the wholesale price. Another designation you might are the “bid/ask” price spread, a term that comes from auction-based transactions. The bid price is what the dealer is willing to pay for inventory and ask is what they will ask to be paid for that item.

Regardless of what its called, there is one price that a dealer or other reseller will buy the item and the other is the price they will sell the item. As in any business where there is a product being sold, the seller buys low and sells high. However, that markup can be different based on various factors.

Determining the Price

Setting these prices require more thought than guessing. The primary references are the price guides published by many companies. Price guides come in various forms from catalogs, auction catalogs, publishers whose market is producing works for the collectors market, or specialized publishers who watch the market on a continual basis and publish their findings.

Although there are a few references, for most dealers, the basis of their pricing begins with a publication entitled The Coin Dealer Newsletter, called the “Grey Sheet” for its grey color. The Grey Sheet surveys the market provides to provide weekly bid and ask wholesale prices for the dealers to use as guidelines. In addition to the Grey Sheet, the same company publishes the Certified Coin Dealer Newsletter, called the Blue Sheet for its use of blue ink, and The Currency Dealer Newsletter, the Green Sheet, for currency. These publications can be purchased by anyone to gauge the market.

Up until the last few years, price guides for collectors have have been limited to the long running A Guide Book of United States Coins, known as the Red Book for its red color, from Whitman Publishing and later joined by the U.S. Coin Digest from Krause Publications and price guides published by CoinWorld (sometimes referred to as “Trends”), the guidelines have opened a bit with the help of technology. Whether you get your guide price from Numismedia, Numismaster whose prices are driven by the Krause database, PCGS whose own market drives their price guide, or by checking prices amongst online dealers, the resources provide more options for collectors not to be surprised when they go to purchase coins or currency.

Another good are to investigate coin prices are auction results. Most auction houses use their websites to advertise their sales online, but also maintain the price realized from their auctions with some having online archives dating back many years. Accessing the prices realized is as simple as registering on the site and searching previous auctions. Like anything on the Internet, some sites are better than others so your experience will differ from site to site. However, the advantage is that rather than guessing based on surveys, you will know exactly what has been paid in the past and can adjust your expectations according. There will be more on the auction process later.

Buying from the U.S. Government

Two agencies within the Department of the Treasury are responsible for the manufacture of money in the United States: the U.S. Mint and Bureau of Engraving and Printing. Both agencies are responsible for supplying the Federal Reserve with the physical currency necessary for the economy. In fact, both the U.S. Mint and BEP sells their products to other governments for use where the U.S. dollar is the standard currency.

Both agencies have collector products they sell to the general public (see the BEP Store and U.S. Mint online Catalog) that are sold at a fixed price. The difference between the two is that the BEP does not produce commemorative or something similar to proof coins, the U.S. Mint does produce coins specifically marketed to collectors and investors. Both agencies will package their regular products in a way to entice collectors to buy them at a premium whether these are Federal Reserve Notes with special numbers, uncut currency, or packaging of uncirculated coins. When these items sell out or withdrawn from their respective catalogs, the collector can buy them from the secondary market.

Dealers

Meet the seller to the secondary market, the dealer. A dealer is someone who will buy coins from collectors, estates, auctions, or other dealers and resell them for a profit to an interested collector. Some dealers sell at wholesale rates (bid or value) to other dealers to move stagnant inventory or to trade inventory in order that both are able to meet their customer’s demands.

Dealers work in different areas of expertise. Some will only deal in raw coins while others will only sell coins in slabs. They will specialize in coin types while others will sell currency, ancient coins, or foreign coins. There are dealers who sell numismatic books, supplies, tokens, bullion, and exonumia. Dealers may also sell jewelry as part of their inventory. If you had to classify most dealers, they are usually small businesses, many with a few employees, whose livelihoods depends on acquiring and turning over inventory.

Although there are suggested prices, as described above, dealers set their own prices on their inventory. They do take into consideration what the price guides say, but they also have to consider what they paid for the coin and what it costs for them to sell that coin. Costs include everything it takes to run the shop from the lease to utilities plus security and employees. The dealer also has to make a profit—after all, they are in business to make money.

Buying at Coin Shows

Coin shows present a different buying experience from dealers in that you have a lot of people to potentially buy from. Even the smallest coin show offers a variety of products that many shops could not replicate and while there is a camaraderie amongst the dealers, they are also in competition with each other. As a buyer or someone who is selling their coins, this is the variety provides many opportunities to get the best price.

The best experience you can have in numismatics is going to a coin show regardless of whether it is a large or small show. As you walk around the bourse floor, look around, talk with the dealers, and talk with other collectors. It is a way to learn more about the hobby and the people in the hobby. Use the opportunity to build a rapport with the dealers. Not only are many the most knowledgable in the industry, but they may offer you discounts if you buy from them based on the recommendations. You can also take the opportunity to shop around to find that perfect coin.

There are all types of dealers who attend shows with a varying type of inventory. At the largest shows, you can meet dealers with a brick-and-mortar presence back home, dealers who just travel to shows to buy and sell, part time dealers who have a regular job during the week and sell at shows on the weekend, and vest pocket dealers who may not have a table but walks the floor and tries to sell their wares. Remember, dealers who travel to these shows have inventory that they bought, travel expenses, and fees for setting up at the show that will factor into their prices.

Mail Order Dealers

Mail order dealers may be as old as the Post Office itself. They grew out of the need to be able to sell to collectors that may not have a coin shop nearby or cannot travel to shows. Lately, a few of the very large mail order dealers have received criticism for their higher pricing structure without considering their business model.

In the last few years, mail order dealers have marketed themselves to new and inexperienced collectors offering various clubs and other promotional items to convince people to collect then retain them as casual collectors. Their business model is similar to any mail order business with catalog production costs, a telephone sales force, and a full shipping staff. Mail order dealers usually do not attend many coin shows but may attend some to set up a table for buying only. Their pricing reflects their business model.

Another service of mail order dealers is that once they get you on their mailing list, they will send coins on approval. This service not only helps the casual collector put together sets of their favorite coins, but it helps those who cannot go to shows or to a coin shop regularly. There is also a cost for this service including postage and the possibility of loss that has to be accounted for in their business model. They still have a market niche and are a way to add to your collection.

Auctions

Auctions are the oldest type of marketplace with the earliest recorded auction occurring in 500 BCE. Numismatic auctions sell goods by offering them for bid, accepting bids, and then selling the item to the highest bidder. Auctions begin with a minimum price and go until a bidding ends with no further bids where the highest bidder is obligated to pay for the item at that price. Some auctions have a reserve price, the minimum price the seller would accept for the item. If the reserve price is not met, the seller can withdraw the item without selling it.

Internet auctions have changed the process by adding a time limit on the sale of a single lot. Rather than wait for the last bidder as with a live auction, the highest bidder at the time of the end of the Internet-based auction purchases the item at their highest bid.

When auctions started, participants had to be present or send an agent in order to bid on the item. As technologies have changed, the nature of bidding has change. The first change was the introduction of the Postal Service that introduced bidding by mail. Bids could be sent by mail or some firms offer auction exclusively by mail called mail bid sales. Telephones added the ability for people to attend an auction from far away by communicating their bid through a representative of the auction company. Some could even contact an auction company and leave a proxy bid for specific auctions. The invention of facsimile technologies added the ability to quickly send proxy bids along with other verification information for those who are not or infrequent customers of the auction company.

Buying and selling via an auction requires payment to the auction company for selling the item. Seller fees are either a fixed price or percentage of the final price of the item sold, also called the price realized. If the item sells, the seller is paid the final price less the seller fees. The buyer pays a buyer’s fee as a percentage of the price realized with an advertised minimum. Seller fees range from 10-15 percent and buyer fees range from 15-20 percent. Sellers can negotiate the seller fees. Buyers are told what the buyer fees as part of the terms of sale and are not negotiable. Buyers may also be required to pay for shipping of items when they are not present at the live auction.

Online auctions are a bit different in that the sellers pay a listing fee and a final value fee based on the price realized. In these venues, sellers bear all of the fees while the buyers pay the price realized plus shipping. Some sellers will add “handling” charges to offset the fees paid as part of the auction.

Negotiating

Negotiating is difficult for some for many reasons. For others, not only can it be fun but there is an additional thrill of being able to negotiate a price. There is no rule that you have to negotiate. You can accept a dealer’s price and either buy or not. However, in my world, everything is negotiable and it is part of the thrill of buying that perfect collectible.

There are no set rules for negotiating and how you negotiate will change with the situation. When purchasing a coin, I will ask the dealer for a price. Depending on the price and situation, I will either pay the price if I think it is a fair price or ask if the dealer could do better. Sometimes I ask if I can offer a lower price. The dealer may come down in price or say that the price is firm. The negotiation continues until either a price is agreed upon or we cannot settle on a price. For those times I am unwilling to pay the dealer’s price, I will always thank the dealer for the time before turning them down.

When negotiating, I follow three guidelines that you might want to consider adopting:

- Be nice. The dealer is a human being and should be treated with the respect shown to anyone else. As you are talking, if you get the feel that you can be a little more aggressive, then do so only if the dealer seems receptive. Do not insult the dealer and do not turn the negotiation into an attack. Do not make it personal, it’s business.

- Do your homework. Before trying to negotiate, you should know the price and value of the coin and be prepared to use those as guidelines. Also, know what the bullion value of the coin is and never offer less than that value for the coin. Trying to buy coins below melt value may be insulting to the dealer and your attempt at negotiating will not be taken seriously. In some cases, it would help to know what is selling in the overall market. At shows I would ask dealers how their sales were doing and what was selling. If a dealer is having a slow show, they may be willing to accept a lower price to make a sale. Once you have the information and talk with a dealer, you have to remember and respect that this is the dealer’s livelihood. Trying to shave pennies off the price may be fun for you but you may make the dealer upset and will refuse to sell the coin.

- Know when to stop. At some point in the negotiation the dealer may decide that they are offering you the best deal and will stop the negotiation. If you are far apart on what you wanted to spend for the item, you may want increase your last offer, but doing that more than once could cause hard feelings. Sometimes, if you are nice (see the first rule), you can turn this last part into a game: “Gee, I am having a hard time deciding.” “I really want the coin but I didn’t want to pay more than x,” where x is a realistic number. If you try this method, do not try more than once. You will either have to buy the coin or walk way.

If you buy the coin, be gracious. You might have paid more than you expected, but you did get that special coin for your collection. It is appropriate to thank the dealer, shake their hand, smile, and be appreciative. Good will is always appreciated and will be remembered the next time you encounter this dealer again.

If you do not buy the coin, be gracious. Thank the dealer for speaking with you and say, “maybe next time.” Do not waste the dealer’s time especially if there are other customers around. While you may be disappointed do not walk away like the dealer just kicked your dog. Who knows, next time may be in a few hours after the coin is still on the dealer’s table at closing time. The dealer may be willing to “work the price further” if they perceive that you are a serious and courteous buyer.

Finally…

Finally, have fun! Unless you are an investor, this is a hobby. Hobbies are supposed to be fun and you can have fun with numismatics. Whether it is the thrill of the chase, finding that special coin, or putting together a great set of coins, you can have even more fun when you are smart about what you buy. To borrow a phrase, Live, Learn, and Collect!

Jan 11, 2012 | coins, education, values

Amongst the questions that are asked of me is what makes one coin worth more than another and why does one dealer charge more than others. The numismatic community was reminded that coin prices can vary based on a lot of conditions when a 1793 Chain Cent was auctioned for $1.38 Million at this year’s F.U.N. show in Orlando, Florida. In this article, I will discuss price and value of coins.

There is a difference between the “price” of a coin and its “value.” The “price” of the coin is what you pay when you buy the coin—sometimes called the retail price. The “value” of the coin is what a dealer will pay you for the coin—also called the wholesale price. Sometimes, the difference between the two concepts frustrates collectors who look at price guides as the price tag of a coin when it is a guideline. Dealers become frustrated because collectors fail to understand the business aspect of buying and selling coins. Hopefully, I can educate both sides.

Factor 1: Supply and Demand

Of all the factors that go into setting prices, the major consideration is supply and demand. While there are a lot of good definitions of the basic laws of supply and demand, in the numismatics industry the supply drives the price harder than the demand. This is because once a coin is minted, it is rare that they will be re-minted. There are exceptions to that rule, such as the 1804 silver dollar and 1942 Mexican Dos Pesos gold coin, but once the mintage period for those coins pass, no more will be struck.

Another factor that drives supply is how many of the coins survived the various melting and recalls that occurred over the years. While there have been many good educated guesses as to how many coins have survived, the only definitive answer are the population reports from the grading services. But those reports may not be accurate because of the number of people who crack the slabs and resubmit the coins hoping they receive a higher grade without reporting this to the grading services.

Supply factors do not apply to the bullion market. Coins minted strictly for their metal content, such as the American Eagles, are usually not affect by the supply. Of course there are exceptions that include the coins associated with American Eagle Anniversary Sets.

Although supply is a significant issue, demand should not be underestimated. The demand is determined by how many of us collectors want to purchase a particular coin. The easiest way to envision how demand drives up the price is to take the classic 1909-S VDB Lincoln Cent. With 484,000 struck by the branch mint in San Francisco, it is the key to completing a Lincoln Cent collection making the demand higher than almost any other coin in the over 100 year old series. Since the supply remains unchanged but the demand increases with the number of new collectors entering the hobby or as collectors could afford a coin, it leads to a higher price.

Factor 2: State of Preservation

Whenever supply and demand is explained to a new collector, they pull out their favorite reference book and point out that the 1914-D Lincoln Cent is worth more than the 1931-S Lincoln Cent even though more 1914-D cents were produced. That is when I bring up the third factor that determines price and value: state of preservation, or as many collectors call it, the coin’s grade.

Coin grading is one of those topics you do not want to bring up in polite company because the differences in opinions are akin to religious discussions—not only is everyone wrong, everyone is right. In other words, contrary to what many are lead to believe there are no right answers. After all, the two top grading services cannot agree amongst themselves. This is why the rest of this article will not discuss grading but use the concept as a relative term.

The higher grade of a coin, the better the state of preservation. The better the state of preservation, the more desirable the coin. Thus, it could be said that the state of preservation decreases the supply. Even if the demand remains the same, when the supply decreases the value increases. In the case of the 1914-D Lincoln Cent, the issue is that the coin did not feature a sharp strike as other coins and finding problem-free coins are difficult. Because the economy of 1914 was not strong, not only was the need to strike new coins were reduced, but citizens were more likely to spend their coins rather than save them. With the weak strike and heavy circulation, the actual supply of desirable collector coins is much lower than its mintage figures suggest.

Although there were fewer 1931-S cents struck (886,000 versus 1.193 million for the 1914-D cent), there are more 1931-S coins that were well struck resulting more desirable coins survived. Although 1931 was near the beginning of The Great Depression, enough coins were produced in the 1920s that the many 1931 coins were spared heavy circulation. In short, the supply of desirable collector coins is closer to its mintage than that of the 1914-S.

State of preservation also considers environmental factors of the coin. Using the copper cents as an example, a cent that still has its red luster as if it came right out of the Mint’s presses is worth more than a similar coin that has tarnished to a red-brown or even dark brown color. Because it is difficult to prevent copper from oxidizing, the number of copper coins (pre-1982) that still have their red color is far less than others lowering the supply for a high demand item. As the coin oxidizes, it joins a larger supply of others and lowers the value.

Similar to the red-to-brown oxidation of copper coins is toning on silver coins. Toning describes the result of the natural oxidation process of the silver-copper or gold-copper alloy used to strike older coins that create a tarnish or patina on the coins. The nature of the alloy can create very colorful toning on the surface of a coin making it more desirable to collectors. The condition that creates toned coins vary and not every coin becomes toned leaving a smaller supply. However, collecting toned coins is a matter of taste which reduces the demand for these coins and lower the expected price of a coin in a smaller supply.

Factor 3: Melt Value

Coins made of precious metals such as gold, silver, or platinum, at a minimum, will be worth the intrinsic value of the metals used in its manufacture. For example, a Morgan dollar was made with an alloy of 90-percent silver, 10-percent copper, and weighs 26.73 grams. Thus, a Morgan dollar contains 24.057 grams of silver and 2.673 grams of copper. Using the current price of silver and copper, known as the spot price, of the metals ($28.81 per troy ounce for silver and $3.3836 per pound of copper), the value of the metals in the Morgan dollar, called the melt value, is $22.30. You should never expect to pay less than the melt value for any coin even for the most common coins. If you find someone who will sell you coins for less than the melt value then please contact me—I am always in the market for a bargain!

Starting in 1965, the United States changed the composition of its coins because the spot price of silver was making the coin’s melt values worth more than their face value. Silver was replaced with a copper-nickel alloy that is still in use today. However, the Kennedy Half Dollars struck from 1965 through 1970 were struck using an alloy that contained 40-percent silver. Also, the U.S. Mint has continued to strike commemorative coins and special sets using silver and gold. These coins use the traditional alloy of 90-percent silver or gold along with 10-percent copper. They were not struck for circulation and are valued in much the same way as circulating coins.

Up until 1982, the Lincoln Cent was struck using an alloy of 95-percent copper and 5-percent zinc weighing 3.11 grams. In 1982, the law was changed to allow the U.S. Mint to strike Lincoln Cents on a copper-coated zinc planchet. The coin is 99.2-percent zinc with .8-percent copper weighing in at 2.50 grams. Since the change occurred in the middle of the year, the U.S. Mint struck coins of both types. Specially packaged sets of these Lincoln Cents are in high supply with a low demand translating into an affordable collectible.

To learn more about the melt values of various U.S. and Canadian coins, you should read the information at coinflation.com.

Factor 4: Artificial Factors

Artificial factors are those that usually detract from a coin’s value. Coins that have been cleaned, doctored, tooled, dipped, whizzed, polished, or any other way that someone can use in an attempt to make the coins better will lessen the coin’s value. At one time, it was acceptable to clean and polish coins to make them look better. One method that was once acceptable to preserve the red color of copper cents was to use clear shellack to coat the coins. Do not clean, polish, scratch, or try to make your coin look better. If the coin has an issue that is not a permanent problem with a coin, you may want to consult a company like Numismatic Conservation Service to find out of professional conservation could save a coin that may have been damaged by accident.

Not only will altering a coin to make a common coin look like a rare coin lower the coin’s value, it is also illegal. Changing mint marks, dates, using a tool to make the coin look like another variety—usually with Morgan Dollars—will make the coin worthless and if you try to sell it as genuine will genuinely land you in jail.

Buffalo Nickels and the Standing Liberty Quarter Dollar were coins whose design did not wear well in circulation. On the Buffalo Nickel, the date was easily worn from the coin. Some people take dateless coin and use a special acid to determine what the date was on the coin. Acid can also be used on the reverse of the 1913 Type 1 Buffalo Nickels to show a mint mark that might have been on the mound the buffalo is standing on. These are known as “acid coins.” Both Buffalo Nickels and Standing Liberty Quarters can be enhanced using engraving tools. These altered coins are worth much less than their counterparts with original, non-altered, surfaces.

Tooling for altered surfaces can have value in certain circumstances. One of these collectibles are Hobo Nickels. The Hobo Nickel is an art for where the surface of a small denomination coin is carved to create a mini work of art. The nickel was the popular coin for its low cost and the softness of the metal. This art form became popular during The Great Depression when Hobos would carve designs in these coins and sell them in order to earn money. Hobo Nickels vary in value depending on the aesthetic value of the artwork and the artist. Two artists of the 1930s, Bertram Wiegand, known as Bert, was the first great Hobo Nickel artist. His student, George Washington Hughes, known as Bo, have both carved Hobo Nickels that have sold for prices equivalent to semi-key date coins.

Another type of tooled coin is a Love Token. The artist who creates a Love Token takes a coin, smooths one side and hand engraves a design. Many of the designs are an expression of love and given to a woman by her suitor. Love Tokens were more popular in the mid 19th century and mostly engraved on Seated Liberty Dimes, although other coins were used. After engraving, holes were punched in the coin or loops added to it in order to turn the new art work into jewelry. Prices vary with the type of material used and the quality of the artwork.

If you are not yet confused, then let’s take a new look at toning. When toning is natural or created accidentally over the years because of environmental factors, these coins are called “naturally toned” and desirable to some collectors. However, natural toning can have detrimental effects such as toning that occurs on coins because they were improperly stored. “Album toning” occurs when the coin is store in an old album that may be made of an acid-based paper that has leached chemicals on the coin. Verdigris is the green “toning” that appears on any coin containing copper that came from being stored in or near plastic that was made with chemical softeners such as polyvinyl chloride (PVC). Toning from improper storage can be ugly and not desirable which will lower the coin’s value.

Those who collect toned coins like the rainbow of colors. However, it is possible for coins to be artificially toned and made to look as if it was naturally toned. Determining the difference between naturally and artificially toned coins can cause an argument whose passion rivals that of a religious debate. Naturally toned coins are worth more to toned coin collectors than artificially toned coins, if you can tell the difference between the two.

Confused?

If you dig further into pricing and exceptions of various numismatic items, determining price can be even more confusing. One area I did not discuss is paper currency, which is never worth less than face value. And this is only half the story. In the next installment, the discussion will look at how this information determines “price” and “value” when you visit a show or a coin dealer.

Earlier this year,

Earlier this year,

Having grown up with

Having grown up with

Regular readers know that I am an advocate of the electronic world, especially when it comes to references that should be available in a more portable manner than paper. While

Regular readers know that I am an advocate of the electronic world, especially when it comes to references that should be available in a more portable manner than paper. While